Michael True: New Ways of Understanding the Culture of Peace

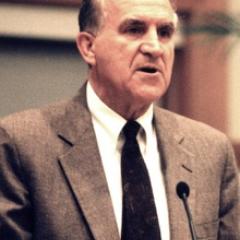

The late Michael True (1933 - 2019) was professor emeritus of English at Assumption College. As a respected authority on the United States’ history of nonviolence, he wrote and edited 10 books, including An Energy Field More Intense Than War: The Nonviolent Tradition and American Literature (1995). This talk served as a keynote panel address at the Center’s February 1999 Cultures of Peace Conference.

Michael True Keynote

Good evening, and welcome to one of the first initiatives centering on the Culture of Peace Programme in New England. Although it may not be an “historic” event (we’ll leave that for history to decide), it is certainly a significant one, for which the following quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s marvelous letter to Whitman, after Emerson’s first reading of Leaves of Grass, seemed appropriate: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career — which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere, for such a start.” This series, and indeed the Culture of Peace Programme announcement, is both a beginning and the culmination of a long effort — looking forward to the creation of a global peace culture in the twenty-first century and looking back to February 1994, in UNESCO — and perhaps further to the first Hague International Conference of Peace in 1899.

It was only a little over a year ago that the U.N. General Assembly adopted Resolution 52/15, proclaiming the year 2000 as the International Year for the Culture of Peace. Then, just six months ago, the General Assembly Resolution 53/25 on the International Decade for a Culture of Peace and Nonviolence for the Children of the World, 2001-2010.

Although some of you may be familiar with these proclamations, I thought that I might begin with a brief summary of the Programme, as outlined in various documents, as a way of calling attention to its very robust conception of peace. At the heart of it, as Michael Wessells has said, “is the view that cooperation across many levels of society and in diverse enterprises — business, education, health care, the arts, and security protection, among others — is essential for healing the wounds of war, for preventing destructive conflict in the future, and for promoting sustainable development.”

The six components of the Programme include goals and strategies which distinguish it from static conceptions of peace that merely perpetuate the violence of the status quo. The basic assumptions and principles are (1) that power is defined not in terms of violence, but of active nonviolence, as represented by proven successes in bringing about social change; (2) that people can be mobilized for justice not in order to defeat an enemy, but in order to build understanding, tolerance, and solidarity — that is, to liberate the oppressor as well as the oppressed; (3) that hierarchical, vertical authorities that characterize the culture of war be replaced by a democratic process that engages people in decision making at all levels and empowers them by the victories they achieve; (4) that secrecy and control of information by the powerful be replaced by participatory democracy, through the sharing of information among everyone involved; (5) that a male-dominated culture be transformed into a culture acknowledging and building upon the special skills that women bring to the peace-building process, with women at the center of institutions emerging from it; and (6) finally, that the exploitation that characterizes the culture of war — slavery, colonialism, economic exploitation — be replaced by cooperation and sustainable development for all.

A central argument of the proposal is that all six principles are essential to a culture of peace; none can be omitted.

Any effort as humane and democratic as the Culture of Peace Programme obviously cannot be realized without enormous effort on the part of people from the grassroots level to the United Nations. And every person across this wide spectrum, that is, each one of us, has a contribution to make. The document clearly delineates a peace culture not as merely a world without war, but as, in Elise Boulding’s words, “a continuous process of nonviolent problem-solving and the creation of institutions that meet the needs” of all people.

A prefatory letter of Frederico Mayor, Director-General of UNESCO, to the Culture of Peace documents calls “the transition from a culture of war to a culture of peace” as “the major challenge at the close of the twentieth century,” and includes an invitation to “every parent and child, teacher and student, reporter and editor, mayor and parliamentarian — in whatever capacity they may contribute — to join together in a global movement for a culture of peace and nonviolence.

“Well,” one might say, “that sounds very nice, but what does it all mean, really? Haven’t we heard this before, in other documents from official agencies that are roundly praised, then roundly ignored by individuals, governments, nations?”

In my remarks, I want to address this skeptical question, highly justified as it may be, by arguing that we have not, indeed, heard anything quite like this proclamation before. In preparing these remarks, I kept asking myself why I responded so immediately to UNESCO’s Culture of Peace initiative, after being disappointed by similar initiatives in the past. I hope that in answering the question for myself, I may offer some useful background and sense of the Programme, to justify our devoting energy and time, from this moment on, to bring it to the attention of a wide audience.

In doing so, I think we might begin by reviewing briefly how we arrived at this place in the struggle for peace. Perhaps you know that, in addition to David Adams, through the Seville Statement on Violence as well as the Culture of Peace, two people on the program with me this evening, Elise Boulding and Paul Joseph, have contributed in significant ways to the development: Elise by her involvement in peace education and research over the past 40 years—the founding of the International Peace Research Association and related NGOs, her book, Building a Global Civil Culture (1988), and a forthcoming book on cultures of peace, and Paul through his work with Peace Studies Association and his recent book, Peace Politics: The United States Between the Old and the New World Orders (1995).

Another person we should make room for, who is not on the program, is someone representing peace activists who have spent many years on the picket line, in demonstrations, and in jail in defending human rights, the environment — a peace culture in the making. For had they not taken those risks, the Culture of Peace Programme would not exist. And furthermore, unless we and others are ready to take similar risks, it is unlikely to take hold on the public imagination or influence politics from the local community to the United Nations.

While it is part of common knowledge that war is a construct, with its laws, strategies, conventions, and defining characteristics, peace remains, for many people, somewhat vague and amorphous.

Michael True

The language of definition and conceptualization throughout the program materials clearly delineate the difference between a war culture and a peace culture. In the past, as it suggests, peace was often defined as merely the absence of war, not as something inherently different, not something “made” or “constructed.” That is, while it is part of common knowledge that war is a construct, with its laws, strategies, conventions, and defining characteristics, peace remains, for many people, somewhat vague and amorphous.

Linguistically, the discussions of the culture of peace are a real breakthrough, for an international and official body, it seems to me, and reflect a struggle that has characterized writing and speaking on that topic since the end of the first World War. Among the many casualties of that “senseless slaughter,” as Ernest Hemingway rightly called it, was the word “peace” itself, which died on the Western Front about 1916. When T. S. Eliot published The Waste Land (1922), for example, he rightly resorted to a foreign word in an effort to name the concept: at the end of his great epic, as the central figure tries to shore up fragments against the ruin of Western culture, he chants not the English word, but its Sanskrit equivalent, “Shantih, shantih, shantih.” Coincidentally, this interesting and symbolic moment in the history of English coincided with the first use of the word “nonviolence.” Seventy-five years later, through the power of nonviolence, as Culture of Peace documents suggest, the word “peace” has at last been reconstituted as a dynamic rather than as a passive entity. Is this not a telling moment in the history of the peace movement, and a sign of its current strength?

The Culture of Peace documents are very clear about how that happened, returning again and again to the central place of individual initiative, nonviolent direct action, people power. At long last, from an international agency, we have an acknowledgement of the folk wisdom that keeps so many of us going in this war culture: the knowledge, in the words of Margaret Mead, (1) that “a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has,” and the words of two bumper stickers that (2) “Everyone makes a difference” and (3) “Peace begins with me.” That may not seem like such a radical perspective; but to have it said not by you or me, but by the United Nations, is something to acknowledge and ponder.

Since the time of Augustine, our culture — and some of the best and brightest among us — has spent volumes arguing and deliberating about what constitutes a just war and what constitutes acceptable or unacceptable behavior in a war culture. The fact that every side in armed conflict regarded its war as “just” renders much of the language of the just war tradition ridiculous, particularly in a nuclear age. Nonetheless, the arguments from “proportionality,” the necessity of declarations by constituted bodies, and so on, remain on the books and are inevitably cited in discussions about whether a war is legitimate or not, in the eyes of the ethicists and moralists, and often of the general population.

Such conventions or guidelines regarding peace have, up to the present time, not been a topic of general discourse. “In the past,” as “The Road to Peace,” a brief summary of the U.N. Programme says, “the struggle for human rights and justice has often been violent. But violence reproduces the culture of war — authoritarian, hierarchical, exploitative, male-dominated, secretive, and above all, mobilized to destroy ‘the enemy.’ We have paid the high price — the lives of millions and millions of people — of this culture of war. Now we must build a culture of peace.” The Culture of Peace, on the other hand, talks about a “new road to peace and social justice — the road of nonviolence.” In doing so, it acknowledges recent initiatives for building peace, saying that “a vast flowering of grassroots initiatives has grown up … initiatives to save the natural environment, to preserve cultural identity and diversity, for education for all throughout life, for the rights of women, and many others.”

It is clear, also, that the Culture of Peace is anxious to make “visible” what has been previously “invisible.” There are heroes all around us, waiting to be discovered. There are role models for tomorrow’s generation in every community, whom we need to seek out and to learn about. You and I know who they are, and part of our work is to make them visible in every way we can: Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, Dom Helder Camara, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, Bernard Lafayette, Dorothy Day, Danielo Dolci, Voices in the Wilderness, Peace Brigades International, United Farm Workers, and so on. As far as organizations and initiatives, looking back only 30 years, we have seen the founding of the Pugwash Conference and the International Peace Research Association, and, among a host of nonviolent initiatives, the overthrow of Marcos in 1983, the democratic uprising in China in 1989, Solidarity in Poland, the end of apartheid in South Africa, the worker/student movement in South Korea, and wherever the effect of citizens groups — Amnesty International, American Friends Service Committee, IPPNW, Witness for Peace, School of Americas Watch — has been felt.

Within the U.N. bureaucracy itself, two important documents are in preparation at the moment: (1) a Manifesto for a Culture of Peace and Nonviolence being drafted by Nobel Laureates and (2) a Declaration and Programme of Action being considered by the U.N. General Assembly. The former is important since it formally commits the U.N. system to work for the culture of peace. The latter is important since up to this time any funding for the program had to come from sources other than the official budget. A further example of the seriousness of the U.N.’s commitment to the culture of peace is a January 1999 speech by Kofi Annan, Secretary General of the United Nations, before the World Economic Forum, asking corporate leaders to embrace, support, and enact a set of core values in the areas of human rights, labor standards, and environmental practice, quite in keeping with the Culture of Peace standard. “Without that commitment,” Mr. Annan said, “there is a danger that universal values will remain little more than fine words — documents whose anniversaries we can celebrate and make speeches about but with limited impact on the lives of ordinary people.”

So it is right and proper, it seems to me, to celebrate this Culture of Peace Programme, to acknowledge an achievement that many of us have had a hand in, and to begin the enormous task of promulgating its message and principles. We have work to do.

By way of summary, I ask you to listen carefully to a poem by Denise Levertov, called “Making Peace.” As a kind of mini-history of the word “peace” in our time, it has a direct bearing on the importance of the Culture of Peace Programme. In a brief dialogue, between someone challenging the poet to “image” peace for him or her, the writer describes the present state of language, acknowledging its limitations for “Making Peace,” yet implying what must be done to transform the present state of affairs:

A voice from the dark called out,

“The poets must give us

imagination of peace, to oust the intense, familiar

imagination of disaster. Peace, not only

the absence of war.”

But peace, like a poem,

is not there ahead of itself,

can’t be imagined before it is made,

can’t be known except

in the words of its making,

grammar of justice,

syntax of mutual aid.

A feeling towards it,

dimly sensing a rhythm, is all we have

until we begin to utter its metaphors,

learning them as we speak.

A line of peace might appear

if we restructured the sentence our lives are making,

revoked its reaffirmation of profit and power,

questioned our needs, allowed

long pauses… .

A cadence of peace might balance its weight

on that different fulcrum; peace, a presence,

an energy field more intense than war,

might pulse then,

stanza by stanza into the world,

each act of living

one of its words, each word

a vibration of light—facets

of the forming crystal.

— Denise Levertov, Breathing the Water (NY: New Directions, 1983)

In our language, and thus our culture, the poem says, peace is not easily imagined, because we don’t know it, really. And, we will not have it until we begin the hard work of “constructing” it. The energy of peace arises from its association with words such as “justice,” “mutual aid,” “questioning,” “restructuring.”

The Culture of Peace Programme focuses, similarly, on the energy and power of peace, a power that arises from the efforts of ordinary people. In that sense, it’s a very practical document, awaiting our commitment and our involvement in utilizing it as a blueprint for nonviolent social change.