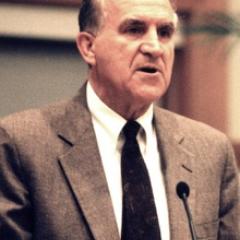

Vito Perrone: Educating for Peace and Social Justice

The late Vito Perrone (1933 - 2011) was Director of Teacher Education at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education when he delivered these acceptance remarks at the Center’s 4th Annual Global Citizen Award ceremony (1998). Among Dr. Perrone’s books is A Letter to Teachers: Reflections on Schooling and the Art of Teaching (1991).

Vito Perrone Remarks

I come before you as an educator and historian of education concerned about children and young people, their families and teachers, their communities and schools

At the end of the last century, the newspapers and journals were full of accounts of progress, especially in relation to industry, technology, and commerce. The twentieth century was previewed as a time of peace and social justice. The new century obviously brought accelerated growth in various technologies and industrial output, but in so many of the things that truly mattered, issues of life and death and matters of the human spirit, the twentieth century has been on the other side of what was predicted. The ravages of war and human displacement, of great hunger and human suffering, have been of overwhelmingly unimagined proportions.

While the large and powerful nations have avoided in the past half-century a full-scale military encounter, the surrogate conflagrations and struggles with new nationalisms have been every bit as devastating as the earlier wars and a peaceful world seems far removed from the peoples of Kosovo, Afghanistan, Rwanda, Liberia, the Congo, Losotho, and the Middle East, and I have hardly covered the globe.

Additionally, the social and economic gaps are enlarging: hunger and inadequate medical resources remain a genuine threat for many millions of people, educational opportunity is far away for large numbers, and religious and political freedom and human dignity are not sufficiently the rule. Even in countries like ours, the economic disparities are growing, poverty is a way of life for too many, educational opportunities are far from equal, homelessness is all around us, and hatreds remain potent.

Our need in the years ahead, certainly in the coming century, is to make a break with those habits of mind, beliefs, and actions that have permitted such conditions to exist, that have left us as individuals and societies so impoverished morally, lacking the will and capacity it seems to imagine other, more equitable, more powerful, more generous possibilities.

Nobel Prize recipient and last year’s Global Citizen honoree, Oscar Arias, made clear in this particular venue, as well as an earlier Harvard commencement address, that a willingness to take risks is always a prerequisite for change because the conventions, the constancies, are so deeply ingrained.

How might those of us who care about education, who still believe that we can educate for a more democratic and humane future, think about this? Let’s put ourselves in the 1840s in the United States and hear again the evangelizers of the common schools describe these emerging institutions as settings in which “all of America’s children could meet, democratic life could be nurtured, strong character built and economic and cultural growth guaranteed.”

Listen to Horace Mann: “If we do not prepare children to become good citizens … imbue their hearts with the love of truth and duty, and a reverence for all things sacred and holy, then our republic must go down to destruction.” We would do well to recapture some of that language, to consider our schools as democratic centers, with students and teachers aiming to make their communities and the world better places in which to live.

I believe with Carlos Fuentes, a Mexican writer and diplomat, when “we say justice, we say development, we say democracy; words won’t bring them, but without the words, they will never exist.” We need the words more than ever.

Unlike so many of his contemporaries at the turn of the century, John Dewey understood that the Industrial Age was producing changes that demanded an education of greater power, that had embedded in it a stronger moral tone, a more extended sense of citizenship, and greater community consciousness.

Because the world has been so violent doesn't mean that we can't imagine a world that is at peace.

Vito Perrone

In Dewey’s terms, we need to see education as a critical path to imagination — that distinctively human capacity to envision a world of greater potential. Because the world has been so violent doesn’t mean that we can’t imagine a world that is at peace, in which nations, like individual families, find ways to reach out to others in need, who see their well-being resting more fully on the well-being of others.

I wish also to acknowledge Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, who has provided considerable intellectual inspiration for the work of the Center. As a contemporary of John Dewey, he expressed similarly provocative ideas. As he understood it, schools need to be places that nurture creativity, happiness, cooperation, a oneness of spirit, connected more fully to the world, to “real life activities.” Makiguchi noted in relation to these aims: “I have to admit to myself that the results of this line of thinking may not be realized in my lifetime. Nonetheless, I have come to burn more and more with a fever to do something, and the sooner the better.” That sense of burning for the better should be within all of us.

The United States is often described as a “microcosm of the world.” Mr. Ikeda, by the way, speaks of the U.S. as the “miniature of the world.” Early in the next century, the majority of school-age students will come from Hispanic, Asian, African, and African American families. We should be celebrating the rich possibilities of this diversity, relishing our place as the crossroad of the world, where people of many nations are converging.

There are pressures to separate students by perceptions of ability, talent, or gift. Such separations, often called tracking, are a means of perpetuating inequities, pitting students against each other, mostly by race and class — which are the primary determinants of academic groupings in the schools. They also lead us to accept the message of test scores rather than to go beyond them.

What if our children and young people learn to read and write but don’t like to and don’t? What if they don’t read the newspapers and magazines, or can’t find beauty in a poem or love story? What if they don’t go as adults to artistic events, don’t listen to a broad range of music, aren’t optimistic about the world and their place in it, don’t notice the trees and the sunset, are indifferent to older citizens, don’t participate in politics or community life, and are physically and psychologically abusive to themselves?

And what if they leave us intolerant, lacking in respect for others who come from different racial and social backgrounds, speak another language, have different ideas or aspirations? Should any of this worry us? If we focused attention here, much might change. Schools might become places that ensure that children and young people possess the skills, knowledge, and dispositions that will enable them to change the world, to construct on their terms new paths.

I ask often: Are our children being provided a basis for active participation in the life of their communities? Are they learning the meaning of social responsibility, of citizenship in the broadest sense? Are they gaining ongoing experience in helping make their communities better places to live?

When I think of schools and citizenship, I often go back to the work of Leonard Covello and his Benjamin Franklin Community School in the early part of this century. This New York City public school committed itself to preparing students to be in the world, seeing themselves as genuine stewards, as real citizens. It is not surprising that students at Benjamin Franklin were involved in citizenship training programs, established community libraries, designed and constructed neighborhood parks, worked on housing drives and land use studies, and conducted health surveys. Why isn’t that the norm in our current schools?

As we move toward the twenty-first century, I wish we were in a better place socially and educationally. The democratic society we need and desire is not yet with us. Education is not the whole of our future and the many imperatives that face us, but it is a central element.

What is the likelihood of schools actually serving students, families, and communities at more powerful levels? It is hard not to have a genuine sense of possibility kept alive when faced each day by the students that I am privileged to work with, whose intellectual and moral commitments are so large.

When I add to that the many thoughtful teachers I see in our schools, and the parents I meet everywhere who are so devoted to an education filled with power and decency, and the young people I observe in the schools who are so caring and so responsible and crave a genuine education, even as they receive little support from adult society, my optimism soars.