2013 Ikeda Forum: Vincent Harding Reflects on "We the People"

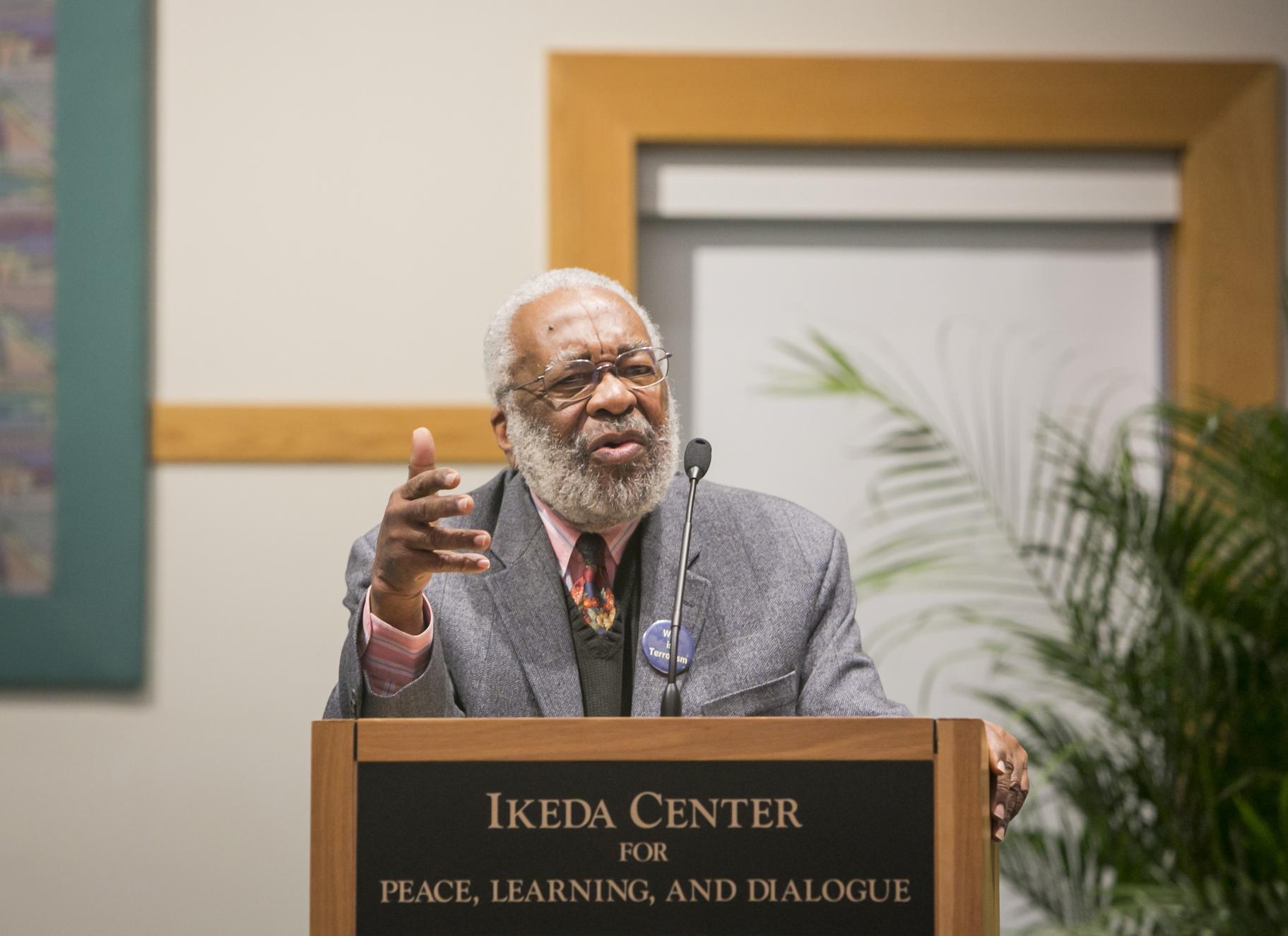

Dr. Vincent Harding speaking at the 2013 Ikeda Forum

At the urging of featured speaker Vincent Harding, the tenth annual Ikeda Forum for Intercultural Dialogue, held in Cambridge on November 9, 2013, became not just a forum devoted to dialogue but also a laboratory devoted to the cultivation of dreams—dreams of freedom and democracy to be precise. The forum, the third in which Dr. Harding has participated*, was called “We the People: Who Are We and What Is Our Work?” This report is by the Center’s Mitch Bogen.

Professor Harding is Chairperson, the Veterans of Hope Project, and Professor Emeritus of Religion and Social Transformation at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver. And he is co-author, with Daisaku Ikeda, of America Will Be! Conversations on Hope, Freedom, and Democracy, the latest publication from the Center’s Dialogue Path Press. The forum also functioned as an author event, with Dr. Harding signing copies of America Will Be! during a post-event reception.

The program opened with a slide show of highlights from the first nine Ikeda Forums and a performance of Friedrich Kuhlau’s “Flute Trio No. 2” by flautists Kanae Kimura, Ayca Cetin, and Kristin Kort. After these features, Dr. Harding was introduced by Ikeda Center senior research fellow Virginia Benson. During her remarks, she recounted the history and evolution of the historian’s relationship with the Center in general and founder Daisaku Ikeda in particular. Having first been alerted, in 1993, to Harding’s work by Emory University scholar of religion Theophus Smith, Center staff immediately determined to find ways of collaborating with Dr. Harding and learning from his wisdom and intimate knowledge of the civil rights movement.

As it turned out, Dr. Harding was planning to visit Japan in early 1994 to see his son, Jonathan, who was studying there. And so on January 17, Dr. Harding and his wife Rosemarie met for two hours with Mr. Ikeda. Benson shared Mr. Ikeda’s remarks on what he perceived in Dr. Harding’s character that day: “I sensed in him the passion of a proud, steadfast champion of human rights and an unbending resolve to battle all forms of prejudice and inhumanity that threaten the dignity and worth of human life.” These qualities have made Professor Harding a treasured member of the Ikeda Center community.

A Laboratory of Hope and Possibility

Stepping up to the podium, Dr. Harding prefaced his remarks, saying: “One of the beautiful things about getting to be 82 years old is that you gather a tremendously loving company of fellow travelers, and I am happy to see so many of you now, who I have I considered my fellow travelers for a long, long time.” He went on to share an insight of one of his fellow travelers (not in attendance), Gus Newport,—like Harding, a member of the Council of Elders **—who not long ago planted in Dr. Harding the seed of a critical idea.

In a message sent to Dr. Harding and the other Elders, Mr. Newport said, in effect, “Please remember that this great American experiment in multiracial democracy is still in the laboratory.” This is significant for a few reasons, said Harding. The word ‘laboratory,’ he explained, is “a word of hope, a word of possibility, and a word of some humility.” Further, the word reminds us that “our task is still with us, and we are with the task.” Perhaps most critically, a lab is where you “are expected to make mistakes.” Thus Dr. Harding encouraged the gathering to not be afraid of “crazy things that have not been tried before” as we work together to create “a truly multiracial, compassionate, peace loving democracy.”

Prof. Harding then offered two illustrations of our ever-unfinished work in the laboratory of democracy. First he shared a song arranged by Bernice Johnson Reagon for her a cappella African-American women’s singing group, Sweet Honey in the Rock. Called “Ella’s Song,” it sets to music actual words from the speeches of the invaluable leader of the movement Ella Jo Baker. The core refrain of the song is “We who believe in freedom cannot rest / We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.” After everyone listened to a recording of the song, Dr. Harding said that he wanted to “take the liberty of changing just one word there. We who believe in democracy cannot rest. We who believe in the possibility of creating a deeply grounded democratic nation cannot rest.”

His second point came in the form of a memory. In the early 60s, Harding was listening to NPR and heard an interview with a young poet from West Africa, where the poet was involved in the struggles against colonialism and engaged in the work of building new societies. In response to a question, the particulars of which Dr. Harding could not recall, the young man said: “I am a citizen of a country that does not yet exist.” This simple idea “became my mantra,” said Dr. Harding, and can motivate our work of building deep democracy.

Harding concluded his formal remarks by addressing one crucial dimension of democracy building, namely the cultivation of dreams. This was a notion expressed well by Langston Hughes, who, in Harding’s words, “like any true creative artist was essentially saying: We cannot have a democratic America unless we first dream it and are willing to take the risks to dream what we have never seen and have been told is impossible.”

The lines of Hughes that Dr. Harding shared with the gathering are also the lines that inspired the title of his dialogue with Mr. Ikeda. “I would like you to listen carefully to Langston as he said ‘America never was America to me,’” requested Harding, then adding: “But he did not stop there. That would be just complaint and protest.” Hughes went further, said Harding, when he declared, “And I swear this oath / America will be!”

Before asking attendees to engage in some dreaming of their own, he shared a poignant example of dreaming among Americans whose lives are lived in difficult circumstances. Just the week before, at another event being held in Cambridge, Dr. Harding listened as a teacher from Washington D.C. shared her experience of asking elementary school children to talk about the schools they dreamed of. “And you will recognize that this is a magnificent question, a loving question,” said Harding, “because it says: We care about you. And we believe that you have something to share. And we believe that you can dream, and we want to hear your dreams.”

The dreams of the children cut to the heart of things. One dreamed of a school where you wouldn’t have to go to the principal’s office to get toilet paper. Another dreamed of a school where the teachers really care about you. These are basic dreams, said Harding, observing that no one else could have dreamed these dreams for these children.

“Hold Fast to Dreams”

For the second half of the forum, Prof. Harding asked attendees to break into small groups to consider an ever-expanding set of dreams: What is your dream of a new neighborhood where you are living now? A new city? A new America? And finally, a new role for America in the world?

To inspire everyone before breaking into their groups, Dr. Harding recalled how his “brother and companion on the way,” Martin Luther King, Jr., kept insisting toward the end of his life: America you must be born again! “What does that mean?” asked Harding. “Is that just some old religious trope?” With that he invited everyone to share their dreams with one another.

After 20 minutes of spirited small group discussion, Dr. Harding invited individuals to share some of the issues and dreams their respective groups wrestled with, explored, or celebrated. For this dialogue portion of the event, attendees did most of the talking, with Dr. Harding frequently offering brief remarks that served to focus and deepen the meaning of their thoughts. What follows is a summary of the dreams shared and discussed during the dialogue session. At Dr. Harding’s request, each speaker mentioned where they were born and grew up.

The first speaker was a young man from New York state whose group dreamed of communities defined by “democratic holism and a sense of sharing,” where differences are appreciated, selflessness is encouraged, and a general spirit of justice “is spread throughout the entire neighborhood.” His remarks were followed by a vision of social well being offered by a young woman who runs a community-based organization in Peru. “I always dream of a neighborhood, a city, a country, a world, and a universe where all of us are able to recognize the value in the other,” which is the “foundation” of everything, she said. She continued:

The minute I walk out my door, I see Langston Hughes’s vision of possibility. That’s what I see every day… . I walk out and see value everywhere. I don’t see the world of violence and sexually abused children that I work with. I see extraordinary teachers … and beautiful things that make me dream even bigger and better dreams, and make me want to work to make them happen.

What a wonderful idea, said Harding, to walk out the door and see what is really around us.

Next to speak was a man who grew up in Brooklyn, but now resides in Cambridge. His group dreamed of a community with no cars, just paths for walking and bicycling; a community where everyone comes out together to see a beautiful sunset. In this community, everyone would look past difference so that people would be seen “as just human beings.” Dr. Harding commended the vision but made a distinction. “Part of who I am is marked by this wonderful brown skin,” he said, “and I want it seen and admired and wondered at, and for people to say, ‘Can we get some more of that?’” So, we should always think in terms of “color appreciation” rather than “color-blindness,” he said. But, “I know what you mean,” he added.

To live in a neighborhood where no one needs keys for their front doors. This was the humble yet ambitious dream of the next group, whose thoughts were shared by two women, both natives of Boston. What would have to happen for us to leave our doors unlocked, they wondered? The bottom line, they concluded, was that “we all have to have some inner transformation for that to happen.”

Their other dream was that “our children and adults keep dreaming,” or, they said, as Hughes phrased it in another poem, “Hold fast to dreams.” Another group member, a teacher, once asked her students to share their dreams, and to her surprise, they didn’t have any. And they were “privileged kids” she added. To which Dr. Harding simply responded, “Without dreams they weren’t privileged.”

Two quick contributions followed. A man with roots in both Mexico City and Maryland shared his group’s dream that we could find a way to really talk about race, and that someone could help us “with all the anger and pain that comes up” when we attempt that. They dreamed of that daunting challenge, but also of “a salsa band on every corner!” A young woman from Taiwan and South Africa discussed her dream of “harmonious coexistence through courageous dialogue,” and talked about how peace and social justice are promoted through the celebrated El Sistema music program, with which she is currently associated.

A young woman from San Francisco said she “dreams that we learn and strive to value others, without pushing our values onto others who already have their own values.” She added that if you do this without dogma and proselytizing then you have a way to help us “move forward as a society.” In response, Dr. Harding wondered if it might be all right to proselytize for joy—a proposition quickly agreed to.

The next speaker was a Massachusetts native who said her group dreamed of a world “where people would openly and freely and joyously communicate themselves.” She contrasted this dream with the reality of her current community where one family—a Muslim family—appears hesitant to open up and get to know others and participate in neighborhood activities. She said she was at a loss as to how to help draw this family out and transcend any fear they might have.

Here, Dr. Harding asked the entire gathering to consider her question and quandary, saying, “I never like for these kinds of questions to be left out in the wind. Part of the joy of community is that somebody that you might never imagine may have some understanding that helps yours.” With that, he invited others to continue the conversation later.

A woman born and raised in Japan reflected on the cultural challenges of being a member of a minority community, as Muslims are in the US. For example, she said, a given Muslim might not feel comfortable at a party that serves alcohol. A peaceful world, she said, requires us “to understand how others view things and what their rules are.” She envisioned a world where “everybody’s life is equal.”

This prompted a reflection from Dr. Harding that revealed his core values. Often we hear people speak of equal rights, he said, but as the prior comments implied, there is something more at stake. He continued:

Sometimes I have wanted us to have deep love and concern for each other, a commitment to each other’s well being. ‘Rights’ is such a legal idea. How do we become more human than that? How shall we consider our sister and brother? We never talk about sisters and brothers having equal rights. We talk about something else. And perhaps we should dream about new language for ways in which to be human with each other, because equal rights won’t cut it. Perhaps it’s a beginning and not the end. So let’s keep dreaming.

Next to speak was a young woman from Cambridge who reflected on how her new residence and neighborhood, though objectively “nice” and even somewhat affluent, is characterized by a sense of isolation, quite unlike the less affluent but more caring and inclusive community she grew up in, where it really did “take a village” to raise a child. Another woman, also from Cambridge, followed up with similar concerns, saying that her dream for her community would be that “people wouldn’t know how much income your family had, based on where you live,” and that children could go to school without being judged on the basis of how much money their families have.”

In response to both, Dr. Harding said, “I really want to tell you how precious it is to hear your dreams and your sorrows…. The village is supposed to encompass all of that. And one dream we can have, he continued, “is to create villages,” even with just “two or three people,” where “we know that there are people who hear us and understand.” Further, in these villages, these communities, we should never forget than we must work together to transform troubling conditions.

As a final note of encouragement for everyone, Prof. Harding said he wanted to “pick up on that other poem that someone mentioned from Langston Hughes”:

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.

“Don’t be afraid of dreams,” insisted Harding. “The capacity to dream is an absolutely human capacity,” he said, and we should also understand that a big part of the work for those of us “who believe in freedom” is that “we cannot rest from dreaming.” Most of all, “don’t let anybody push us so far down that we are unwilling or unable to dream—for ourselves and for our neighbors.”

In conclusion, Dr. Harding invited everyone to sing a variation on the old African-American spiritual “We Are Climbing Jacob’s Ladder.” One verse went: “Courage sisters, don’t get weary / Courage brothers, don’t get weary / Courage people, don’t get weary / Though the way be long.”

Events manager Kevin Maher brought the forum to a close with some words of Dr. Harding’s from America Will Be!: “Hearing many stories helps us to understand our origins, where we’ve come from. But on a more poetic level, these stories help us to understand that we are all parts of one whole—there is no real separation.”

Notes

* Dr. Harding was a panelist at the 2008 Ikeda Forum, “Living With Mortality: How Our Experiences With Death Change Us,” and the 2010 Ikeda Forum, “This Noble Experiment: Developing the Democratic Spirit.”

** According to their website, the National Council of Elders is composed of “veterans of the Civil Rights, Women’s, Peace, Environmental, LGBTQ, Immigrant Justice, Labor Rights and other movements of the last 60 years.” Their founding gathering took place in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 2012. At that time, the Elders said: “We have come together in Greensboro, the birthplace of the Sit-in Movement in 1960, to birth a movement that can share the torch of freedom, justice, peace, and non-violent action with those who have risen anew in the 21st century.” Much of the work to date has been in support of the Occupy movement.

Photos by Marilyn Humphries