2010 Ikeda Forum: Developing the Democratic Spirit

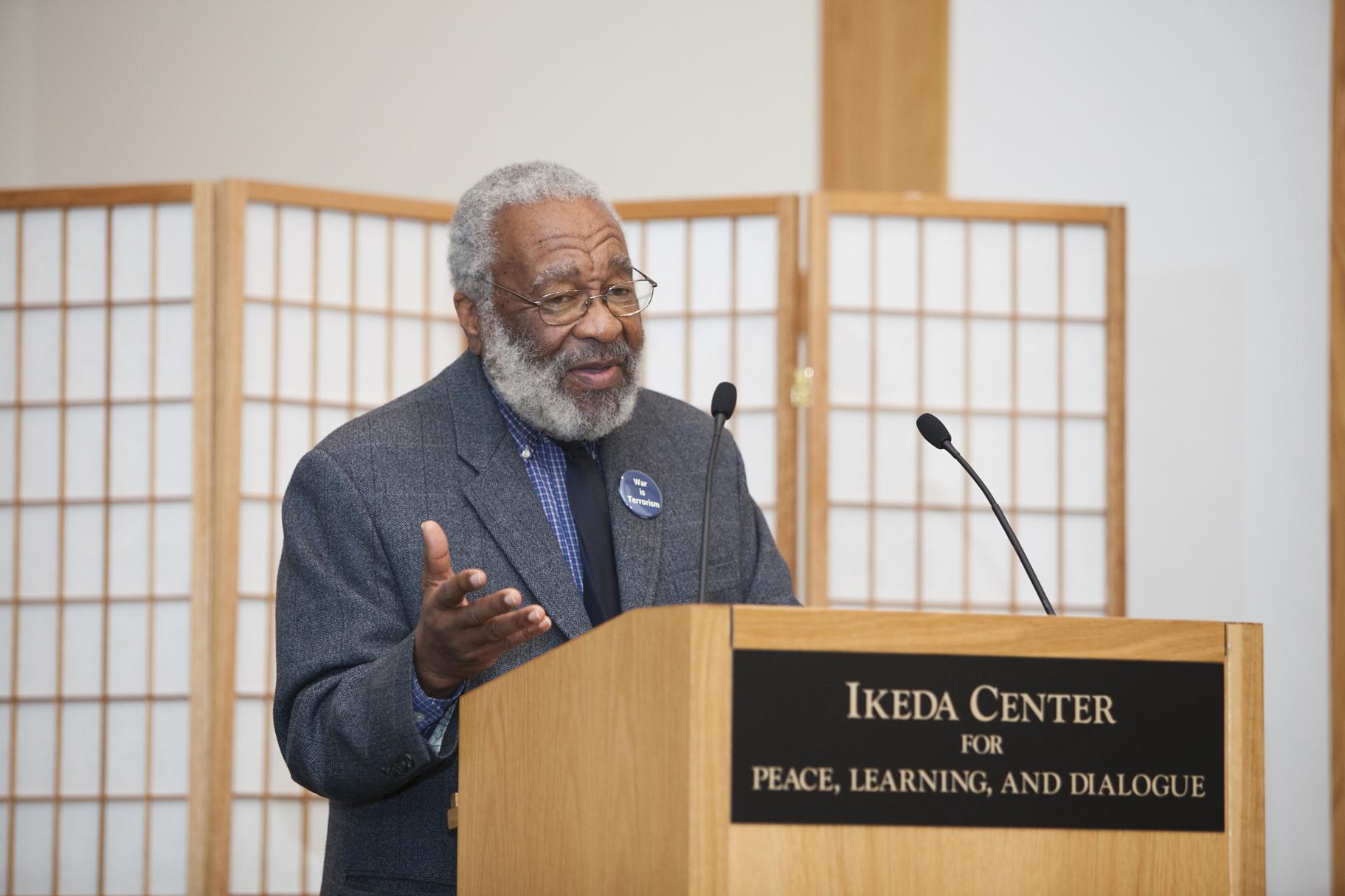

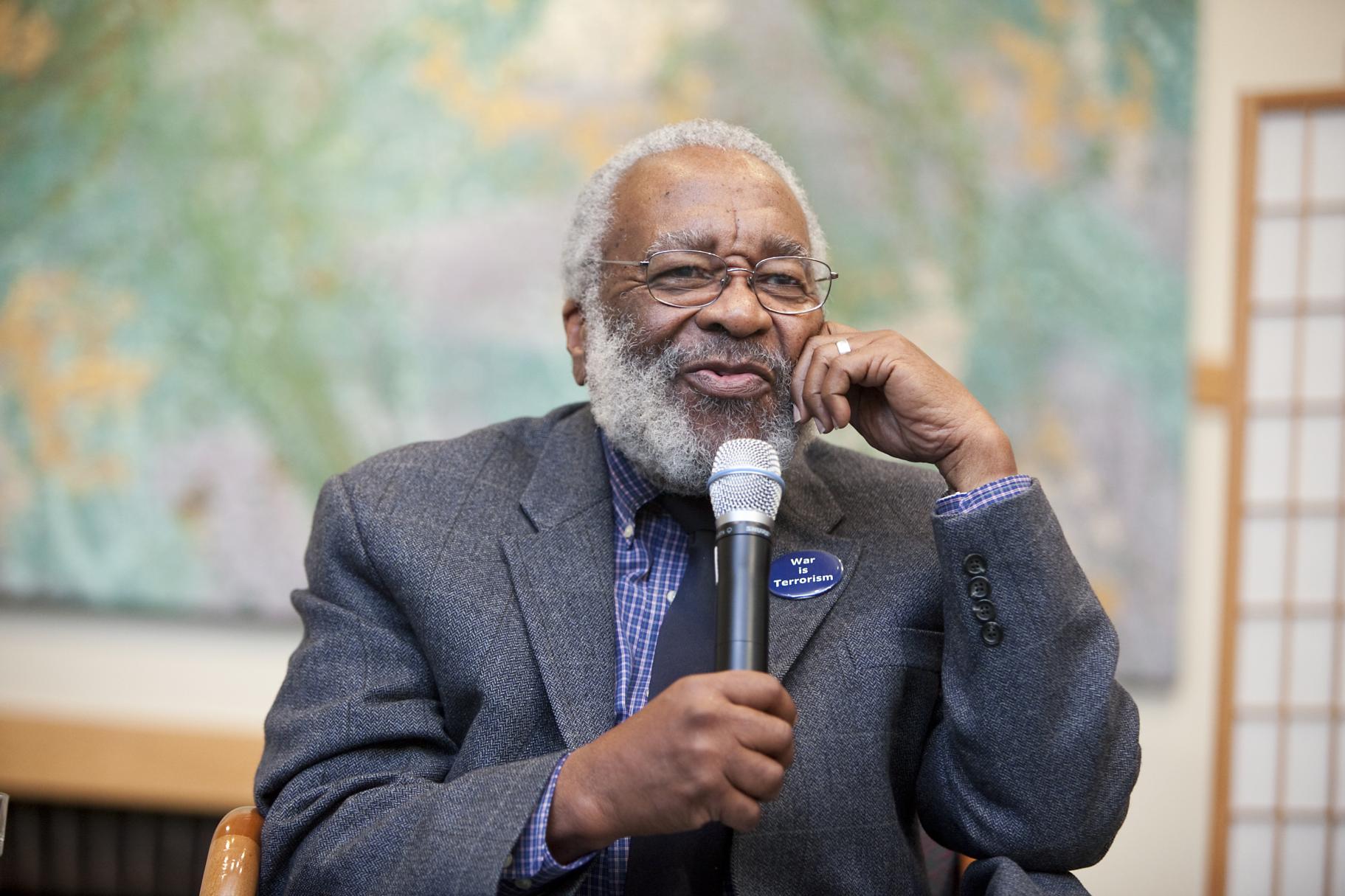

2010 Ikeda Forum panelists respond to audience questions during the Q&A

On Saturday, November 6, just a few days after millions of Americans had voted in the midterm elections, a capacity crowd gathered at the Ikeda Center in Cambridge, MA, to consider how we might further develop the democratic spirit, a process and goal at once more subtle and ambitious than the casting of ballots.

Drawing inspiration from Daisaku Ikeda’s remarks on democracy found in his message commemorating the first Commencement ceremony of Soka University of America (2005), the Center’s seventh annual Ikeda Forum for Intercultural Dialogue—called “This Noble Experiment: Developing the Democratic Spirit”—explored democracy not as a form of government but, in Ikeda’s words, “as a way of life whose purpose is to enable people to achieve spiritual autonomy, live in mutual respect, and enjoy happiness.”

Electoral results may or may not contribute to these goals, explained the day’s six presenters: LR Berger, Virginia Benson, Sarah Wider, Fernando Reimers, Anita Patterson, and Vincent Harding. But one thing is clear, they agreed. Every effort to develop the democratic spirit requires us to draw out and develop our finest attributes—and to help others to do the same. Perhaps this is why Mr. Ikeda, building on John Dewey’s idea that the effort to achieve democracy is humanity’s “greatest experiment,” adds that this great experiment should also be understood as a noble one.

Poetry, Spirituality, and the Democratic Spirit

The Forum’s morning presentations emphasized the spiritual and poetic qualities of the democratic spirit. Speaking first was LR Berger, an award-winning poet and New England Associate for Pace e Bene Nonviolence Service. She offered a unique insight from the Jesuit priest, peace activist, and author John Dear, who says that “violence is forgetting who we are” as humans. If that is true, said Berger, then “the health of democracy depends on remembering who we are, individually and collectively.” It means calling forward our true humanity and inviting in those who have been “forgotten, violated, diminished, shut out of the human circle.”

She then shared several poems, including “Democracy” (1949) by the great African-American poet of the Harlem Renaissance Langston Hughes. It laid out two key themes of the day. First, the appeal to our best selves: “Democracy will not come / Today, this year / Nor ever / Through compromise and fear.” And next, the notion that true democracy means nothing less than the ongoing inclusion of all persons in its process and promise, not least those long excluded because of their race: “Freedom / Is a strong seed / Planted / In a great need. / … I live here, too. / I want freedom / Just as you.”

Next to speak was Virginia Benson, Senior Research Fellow at the Ikeda Center. She drew special attention to the influence of Walt Whitman, the seminal American poet of the 19th century who embodied and communicated the essence of the democratic spirit. Acknowledging Whitman’s impact on Daisaku Ikeda, Benson noted that the faith in “the equal spiritual dignity of all life” that is central to Whitman is also central to the Lotus Sutra, the teaching on which Ikeda’s Buddhist philosophy is based. True democracy, Benson said, must always spring forth from the inherent dignity of humanity, in all its diversity, and for that reason can never be imposed from outside or above.

She also contrasted Ikeda’s three goals of the democratic way of life—achieving spiritual autonomy, living in mutual respect, enjoying happiness—with “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” the three “unalienable rights” enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. Her discussion of living in mutual respect identified what often is missing in the American conception of democratic life: Given our “rather materialistic, competitive culture,” those unalienable rights easily become license for rampant individualism. Mutual respect demands more of us, said Benson. It calls us to “interact with others in a way that brings out the best qualities” of all with whom we engage.

Concluding the morning session was Sarah Wider, Professor of English and Women’s Studies at Colgate University, and currently a dialogue partner with Daisaku Ikeda. Referencing a well-loved poem by Emily Dickinson, Wider titled her talk “Dwelling in Possibility: Poetry’s Noble Experiment.” In Wider’s view, poetry excels at calling forth the ideas and insights needed to enrich our world and support the democratic spirit. She quoted the poet Audre Lorde: “For it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are, until the poem, nameless and formless, about to be birthed but already felt.”

And she cited Daisaku Ikeda’s Choose Hope dialogue (with David Krieger), asserting that the poetic spirit not only calls forth vital human qualities; it also preserves them in the face of what Ikeda calls “the mechanizing effect of the nation-state system and its authoritarian theories.” Instead of living in the nation state, wondered Wider, “what if we lived in that poetic state? Valuing connection, eyes wide open to its multiplicity; ears open to its manifold music. Listening with all our being.”

Democracy and Education

Following a performance by jazz musicians Emi Inaba, Malcolm Parson, and Tameeka Colón, Fernando Reimers launched the afternoon sessions with an exploration of the close relationship between democratic and global citizenship education. As Ford Foundation Professor of International Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Reimers observes and works with educators worldwide.

Citing the example of Finland, where students score high on academic measures but also receive a thorough education in ethics and civic participation, he lamented the narrowed vision of public education in the United States, where test and career preparation now take precedence over other concerns. “What has happened to our expansive vision of education,” Reimers wondered, the one where the promotion of peace and human rights is not an expendable goal, but instead forms the heart of the learning experience?

Without a broadening of our vision, and a reclaiming of education as primarily a moral and ethical endeavor, said Reimers, Americans will be poorly positioned to help steer globalization in a positive direction, much less enhance the civic well-being of the United States. We need only look to the current financial crisis, he said, to see that we have been “educating people who are capable of abusing the public trust.”

Speaking next, Anita Patterson, Associate Professor of English at Boston University, confirmed that many students enter her literature classroom more concerned with its relevance to their career goals than how it might enrich their lives. But through the careful creation of an open and respectful classroom environment, students soon feel free and safe enough to open up and participate in what Emerson called “a society of minds.” In so doing, said Patterson, “young people learn … values needed for the healthy flourishing of civil society.”

Not least among these values is a commitment to bridging the “cultural, racial, and class divides” that inhibit the emergence of true democracy. The towering African-American intellectual W.E.B. DuBois, said Patterson, held this purpose of education in especially high regard, referring to the enlightened atmosphere of the liberal arts classroom as nothing less than a “green oasis” in “a wide desert of caste and proscription,” a place where people can “listen and learn of a future fuller than the past.”

Patterson then confirmed that the beauty of the classroom dedicated to open dialogue is real, if hard to quantify. “It has been my experience,” Patterson said, “that, regardless of their final grades, students like to talk in class; and that talking, in turn, helps them to set aside their bitterness, fear, or disappointment and look ahead toward a better future.”

Citizens of a Country That Does Not Yet Exist

The event culminated with an extraordinary talk from Vincent Harding, Professor Emeritus of Religion and Social Change at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado, and co-founder and chairperson, the Veterans of Hope Project. He is also currently a dialogue partner with Daisaku Ikeda. Significantly, Dr. Harding was a friend and confidant of Martin Luther King, Jr. during the years of what Harding always calls “the Black-led freedom movement” or “the movement to expand democracy”—not the more common “civil rights movement.”

Civil rights such as the right to vote, said Harding, are certainly important, but represent only a narrow dimension of what motivated the participants in the movement. To illustrate the truest, deepest motivation for the movement, he played for the gathering a recording by Sweet Honey in the Rock of “Ella’s Song,” composed by Bernice Johnson Reagon and dedicated to Ella Baker, one of the many dynamic women leaders of the movement: “We who believe in freedom cannot rest,” go the lyrics. “We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.”

It was the ideals of freedom and equality, said Harding, imbedded in the Declaration of Independence—yet, as of the mid-20th century, unrealized for African-Americans and so many other Americans as well—that carried sufficient moral and spiritual force to encourage these descendents of slaves to organize and insist, at considerable personal risk, on difficult personal, social, and political changes in America. Harding said it was the desire for freedom in the deepest sense that triggered for Black Americans what Daisaku Ikeda calls “the unleashing of inherent capacities.” Brought forward was the spirit that said to the world, recalled Harding, “We will not stay down there,” shut off from America’s promise of equality and opportunity. “That is not the calling of human beings.”

Furthermore, this spirit did not aim only at the elevation of African-Americans, but rather at the uplift of all Americans—including white Americans trapped and stunted in their role as oppressor, severed from the nourishing qualities of empathy and human connection. Through their actions, said Harding, these “children of sharecroppers” gave new meaning to and brought to life the words of Langston Hughes: “O, yes, / I say it plain, / America never was America to me, / And yet I swear this oath— / America will be!”

And so it was, continued Harding, that those whose freedom had been denied for centuries enacted “the 20th century’s most powerful manifestation” of the democratic spirit. “What could be more noble,” he asked, “than the experiment that says that those who were brought by force to this country as slaves determined to become its greatest teachers of freedom? What a noble experiment!”

And years later, observed Harding, when protesters and insurgents from Prague to Tianemen Square invoked and sang the profound hymn of the movement, “We Shall Overcome,” it demonstrated that the noble spirit animating that song was a universal one, unlimited in its potential to inspire new forms and phases of our experiments in democracy. Today, said Harding, our task is to remember that what Dr. King said way back in the 1950s: “No social advance rolls in on the wheels of inevitability. Every step toward the goal of justice requires sacrifice, suffering, and struggle.”

To illustrate, Dr. Harding shared a memory from the 1960s of a young poet from West Africa speaking on the radio about the ongoing struggles of his people for independence from colonial rule. “This young man said,” recalled Harding, “ ‘I am a citizen of a country that does not yet exist.’ And I’ve never forgotten that, because I think that it’s an idea for us all: I’m a citizen of a country that does not yet exist.”

To close, Harding shared his hope “that this country that does not yet exist will be brought into existence as we go together and find the new possibilities of the great and noble experiment.”

Engaging In Dialogue

As with all Ikeda Forums, attendees engaged in dialogue with one another and with the speakers, bringing fresh ideas and energy to the proceedings. A few key themes emerged during the Q & A sessions with the speakers:

Anger, Empathy, and Poetry’s Dialogical Role

Much of the discussion concluding the morning session centered on whether anger can play a constructive role in poetry and in democratic dialogue and discussion. Referring specifically to LR Berger’s poem “The Poet and the President,” Fernando Reimers wondered if the poem’s tone was “too adversarial,” demonstrating a lack of empathy for the president whose decisions about going to war the poem was disputing. Berger replied that she had wrestled with that very question but decided to include the poem, in part because it had proven quite effective in sparking discussion and dialogue on college campuses.

Sarah Wider observed that a great value of poetry is its ability to communicate the truth of a particular place and circumstance. It does not diminish a poem’s value, she said, to acknowledge that its perspective might in some ways be limited. Virginia Benson added that Daisaku Ikeda does not see a contradiction between forceful language employed in the face of great injustice and the larger practice of dialogue. It is also true, she added, that finding the proper balance between anger and empathy is a challenge that deserves our ongoing, conscientious attention.

Democracy, Education, and the Marketplace

Following the afternoon presentations on democracy and education, professors Reimers and Patterson were asked about the tension between the ideals of liberal arts/peace education and the demands of the marketplace. Anita Patterson said that she is frank with her students that the greatest benefits of engaging with literature generally are not aimed at career growth but rather at the growth and expansion of one’s humanity. Fernando Reimers said that he challenges students’ tendency to consider only the short-term consequences of their decisions. Quite simply, he urges them to live for purposes larger than the advancement of one’s career. He also reminds them that globalization is not only a process of economic integration, but also a process of integrating our hearts and minds as we develop the values that will enable us to live together peacefully and well.

Civic Participation In “This Noble Experiment”

During a substantial Q & A session, Vincent Harding responded to questions that allowed him to reflect on 1) the nature of citizenship education, 2) the costs of participation in the “noble experiment,” and 3) the role of immigrants within this experiment.

1. Harding urged those gathered not only to learn from the example of the citizen education workshops of the Black-led freedom movement but also to imagine what citizenship education should look like in this particular place and time. He observed that the rise of the controversial Tea Party movement in the United States offers an excellent opportunity for all Americans to engage in public dialogue about the meaning of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Referring back to the earlier discussion on market values and education, Harding made the pointed and ironic observation that since African-Americans were first brought to this continent for their “marketable skills,” being useful in the market might not be the best ambition for students.

2. Asked about the costs of “this noble experiment,” Harding replied that one of the main costs is having to spend time “not being certain.” It is “a prelude to maturity,” he said, to learn how to wait, to listen, to explore. In this time of great cultural and economic change in this country, some extremists say they want to “take back our country.” Such people are frightened, said Harding, adding that, on one level, their ideas must be confronted as dangerous, but on another level these people “are in need of great compassion.”

3. Harding said that, without a doubt, immigrants of all types have a role to play in building our democracy. Even the immigrants referred to as “illegal” have a responsibility to contribute to the redefining and remaking of America into the country it must become.

Hope Still Has Wings

The event neared its conclusion with a brief session in which the speakers offered final reflections on the day. After their comments, they were joined by one of the event’s younger attendees (a local high school student), who had been inspired to compose his own poem in response to the ideas and energy he had experienced during the day.

Then, the event ended like it opened: with LR Berger offering poetic reflections on the theme of the democratic spirit. Taking the podium, she extended the spirit of spontaneity by inviting to the stage another young man, who had shared earlier that, as a mathematician, he was only just beginning to appreciate the power and value of poetry. Together they read a poem by Tom Chandler that recalled Emily Dickinson and echoed the philosophy of value creation that inspires the Ikeda Center’s work. “After all we’ve been through,” they read, “and before all that’s just about to happen, / who would’ve thought that hope still has wings?”

Once again, the Center’s Kevin Maher introduced the speakers and moderated whole group exchanges. To conclude, Ikeda Center President and Executive Director Richard Yoshimachi expressed gratitude for the noble contributions of all involved.

Photos by Marilyn Humphries