A Report From the Third Annual Global Citizens Seminar

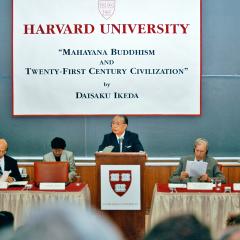

For its third annual Global Citizens seminar, the Ikeda Center hosted eight Boston-area doctoral students for a two-session discussion of the ways that their research areas intersect with the global peacebuilding ethos of Center founder Daisaku Ikeda. For this iteration of the seminar, which was held on June 16 and 30 as part of the Center’s 30th anniversary year slate of events, participants engaged with the central ideas in Mr. Ikeda’s 1993 Harvard lecture, “Mahayana Buddhism and 21st Century Civilization.”

The scholar-facilitators for the discussions were Karen Ross, Associate Professor, Department of Conflict Resolution, Human Security, and Global Governance at UMass Boston, and Jason Goulah, Professor of Bilingual-Bicultural Education and Director of the Institute for Daisaku Ikeda Studies in Education at DePaul University. Dr. Goulah is also Executive Advisor to the Ikeda Center. They were joined by: Seda Akbiyik of the Department of Psychology at Harvard University; Bailey Buchanan of the Harvard Graduate School of Education; Sakshi Khurana of the Value-Creating Education for Global Citizenship at DePaul University; Emily Su Ni Thoman of the Social Policy program at Brandeis; Ahmed Zikrallah of the Research Laboratory of Electronics at M.I.T.; and Khong Meng Her, Kim Soun Ty, and Linh-Phương Vũ of the School for Global Inclusion and Development at UMass Boston.

The first session of the seminar was devoted entirely to the moderators and participants sharing in some detail their personal stories, ranging from their personal and cultural roots to their educational journeys to their current areas of research, interest, and concern. This session was both instructive and inspiring, with many common themes emerging despite participants hailing from or having immediate family in many different countries around the world. First of all, the stories revealed a close relationship between the individual’s personal narrative and their research, with “the personal” representing each individual’s unique response to the world as well as the particularities of experience deriving from their cultural foundations, with many people citing the influence of their ancestors, especially their grandparents. Understood in this manner, identity becomes a creative endeavor and the site of potential value creation. Difference itself also becomes a source of value creation, with new perspectives enriching our perceptions of what society can be in the fullest sense. Or, as one participant put it, diverse experiences thus become a source of nourishment. Finally, each young scholar revealed themselves to be in the midst of an ongoing journey of discovery, with much dynamism emerging from the curiosity characteristic of their liminal states of being.

Grappling With the Big Questions

Welcoming back everyone for the second session, Dr. Ross remarked “how powerful it was to just spend that time together hearing one another’s stories, and I think Jay and I both felt that this [activity] embodied the essence of the kind of dialogue and the kind of global interconnectedness that Ikeda talks about.” Dr. Goulah followed with a few words about the Harvard lecture in particular and Ikeda’s writings in general, saying “I think all of his work is about how do you actualize it.” It might even introduce different ways of “viewing the world [and] our life-scapes,” including “what we’re doing, our spheres of influence, and our practices.” After these introductory thoughts, participants engaged in a paired discussion on global citizenship and themes from the lecture, which was followed by a whole group dialogue that centered on three major themes: life and death, the individual and society, and the meanings and implications of global citizenship.

Life and Death

The session two whole group dialogue opened with a discussion of Ikeda’s views on life and death, specifically on how we develop a culture “that does not disown death, but directly confronts and correctly positions death within a larger living context.” But, as the first person to speak on the topic observed, if we want to talk to children about mortality, which seems essential to the overall goal, it somehow seems too “gloomy” of a subject to broach with them. In response, two of the participants with roots in Southeast Asia, offered helpful perspectives on the matter. For so many from that part of the world, violence and death have been a tragic aspect of life for the majority of residents. So simple denial of death isn’t possible. In fact, said one, “it’s not good to censor those conversations,” an imperative that also applies to Asian children in the US growing up in the presence of anti-Asian violence, they added. Another shared the perspective that in the village life of her native Vietnam, death was “a joyous occasion” in which everyone in the village celebrated the life of the deceased, something she witnessed upon the death of her grandmother.

Is it our excessive individualism here in the US that makes death so difficult, wondered another? Is it our isolation that causes death to frighten us? Another aspect of US culture that might come into play here, suggested Karen Ross, is the tendency to slot things into a “good-bad binary.” Thus, “life is good and death is not; joy is good and suffering is not.” We try to separate out the not-good and ignore the fundamental interdependence of existence. In this vein, another participant added that we rarely see life and its experiences on a continuum, for example, helping a child to see that “even if they make a mistake that doesn’t make you a bad person.” After other participants shared about the range of cultural practices they have experienced in relation to death, Jason Goulah observed that for Ikeda, there is not “one supra-cultural practice” that he recommends in relation to death, but rather our collective “reimagining [of] the full possibility of the human species.”

Individual and Society

In terms of realizing our full possibilities, Goulah said that for Daisaku Ikeda we should take care not to over-emphasize the meaning of external or macro-level change in making this happen. Always, what he recommends is inner transformation, or “human revolution,” as the starting point and primary means of effecting external, social transformation. Because of innate interdependence, inner change will naturally influence the outer. This is all well and good, observed one participant, but if someone “needs to work six jobs” just to get by, where is the space for doing that inner work? Isn’t some sort of systemic change needed? And given that, what does Ikeda say in this regard? Goulah responded that Ikeda does discuss and recommend specific policies in his annual Peace Proposals, frequently addressing matters such as climate change and nuclear disarmament. However, in the most “fundamental sense,” what Ikeda advocates is judging all of our systems and policies by the standard of whether they are actually “serving humanity in the most humane way.” For example, Ikeda discusses economics not in terms of categories such as capitalism or socialism, but instead in the context of what he calls “human economics.”

The meaning and role of happiness arose when one participant, referencing the Buddha’s wish, cited in the lecture, that all beings be “happy and at ease,” wondered about the people of privilege that she knew who were apparently totally “at ease” and perhaps even too comfortable with their lives. In response, Goulah noted that we might never know what a privileged person may be suffering, in terms of illness or loss or any other dimension. But the main thing to know about the happiness Ikeda speaks about is what Goulah calls “existential happiness,” or the kind of deep happiness that is not dependent on the “whimsy” of ephemeral external conditions. “At the core of existential happiness, said Goulah, is the practice of value creation, which, in the ethos developed by Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, means we judge our actions in terms of the extent to which they balance sensorial or aesthetic beauty, individual gain, and social good. Since, no matter the circumstance, something can always be achieved in these domains, “at the level of deep interiority” we are never “deadlocked,” and this is a great source of happiness.

Global Citizenship

For the second half of the discussion, the focus turned to global citizenship, with resonances from the earlier discussion carrying through. As a generative activity, participants first engaged in paired discussion on the topic. One of the first topics to emerge was a simple definition of a global citizen. Isn’t everyone just “inherently a global citizen” without traveling or dialoging internationally? The person raising this question was thinking of her grandmother, “who never left her own people.” Yet, she was compassionate with her neighbors and kind and loving to all she encountered. This question is actually one that Mr. Ikeda addresses directly in his 1996 Teachers College lecture, said Center Executive Kevin Maher. In it, he included those who have never traveled abroad at all, yet who “possess an inner nobility” and “are genuinely concerned for the peace and prosperity of the world.”

Another participant asked an intriguing question that inspired Goulah to go deeper into Ikeda’s thoughts on global citizenship: What is the difference, she wondered, between a global citizen and a Good Samaritan? Acknowledging this as a good question, Goulah shared what we do know about Ikeda’s conception of the former. In the aforementioned Teachers College lecture, Ikeda defined global citizenship in terms of three actions or orientations that can be practiced by anyone anywhere. Specifically these are the wisdom to perceive the interconnectedness of all life; the courage not to fear or deny difference, but to grow through encounters with it; and the courage to maintain an imaginative empathy extending even to those who suffer in distant places. Given these goals, added Goulah, global citizenship can be practiced from anywhere and everything becomes “an exercise in inner transformation toward good.”

Picking up on the question of what we mean by citizenship, another participant shared how, as a native of Texas, her idea of a good citizen is quite different than the prevailing opinion there and in Florida, where social and political developments run counter to everything she believes in. So what, really, does it mean to “be a good citizen”? Dr. Ross responded that language or terminology can “constrain” us sometimes, so maybe the thing to do is focus on “the operative principle,” which in this case would be the courage to engage with difference. Looked at this way, one might ask: What causes someone to have a different set of values? And this is where dialogue comes in, she said, adding that “maybe the person next to you has experienced life in vastly different ways than you.” Another participant added that because of the wide range of value systems in the world, it’s “very hard to pinpoint inherently good and bad things or ways of living.” Given this, said another, when we talk about “the good” or goodness, we should remain aware that it is the “dignity of life that is at the center.” Another added that we might also use social justice as a standard, recalling how, in the lecture, Ikeda also speaks of the mode of dialogue in which “speech must be like a breath of fire.” In this mode, she said, a speaker might challenge us to answer the fundamental question: Who belongs and who doesn’t?

On the topic of good, another said that she finds that the “obsession with being good is a very interesting phenomenon that exists.” Sometimes the need to be perceived as good is so great that it becomes a function of the ego in which one needs to be seen as a savior. On an international level one could look at the way a country like the US might provide aid to a country and in so doing appear virtuous, she said, all the while ignoring the ways that the country may have engaged in other activities that contributed to that country’s instability. On a personal level, one participant noted that it can be “tiring” to be the one who “breathes fire” and is always outward oriented for the good of others. Could it be that the best way for her to be a global citizen is through self-care? “I’m in this current state,” she said, where I’m “preserving energy because that’s how I’m able to contribute myself fully in a positive, good way to the people around me who matter.”

Conclusion: On Dialogue

The seminar concluded with participants sharing thoughts on dialogue itself. For Daisaku Ikeda, said Kevin Maher, “the significance of coming together in dialogue is to learn from each other. It’s not always with the intention of I’m going to change your mind,” unlike on social media where people frequently just “shower you with facts to prove that you’re wrong,” adding how “that doesn’t actually change anyone’s hearts.” Rather, for him, and for the Center as well, it is “the act of coming together and hearing other stories” that matters, “which to me was enacted so beautifully in the first session.” One participant followed up saying that, in this model, dialogue is a “weaving of the community together,” like a “net.” Another envisioned dialogue of the sort engaged in during the seminar as a widening of circles, where you “get to be in dialogue with people” beyond those you normally “grapple with these issues with,” such as family and close friends. So it’s been an “interesting experience and very unique,” she said.

As the seminar moved toward wrapping up, Center Program Manager Lillian I remarked how powerful it was for her to hear all of the stories shared during session one. They really showed that we each “have our own unique set of circumstances that enable us to fulfill our own unique mission in the world.” These thoughts served as prelude to closing reflections from Maher, who shared a quote from Daisaku Ikeda’s 2009 message to the Center in which he championed what he calls the greater self.

Our objective must be the realization of peace for all people and to support the harmony and progress of global civil society. The way to achieve this, I believe, is, again, through the dialogue of spiritual openness. The key to such dialogue is devoting our very lives to listening and learning from those different from us. This humble willingness to learn is profoundly meaningful, invariably fostering deep, empathetic connections. Not only does this resonance enable us to understand others on a deeper level, it acts as a mighty impetus for our true self — our greater self — to flower within us.

To me, this is “global citizenship,” said Maher, and “it’s an orientation toward life” that is profoundly “meaningful” and “joyful” – and “needed now more than ever.” With that he thanked everyone for “taking the time for these two sessions and for your thoughts and perspectives,” and most of all, “for just sharing yourselves.”