Virginia Benson Discusses the Center's First Ten Years

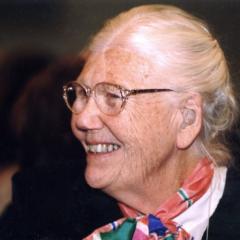

Virginia Straus Benson directed the Center from its founding in 1993 to 2009, served as Senior Research Fellow from 2009 to 2017, and again served as Executive Director from 2017 to 2021. In this 2003 interview with Patti Marxsen, Benson reflects on what she learned during her first ten years as Executive Director of the Center.

How did the BRC come about in 1993 and what was the original vision for it?

The Center was founded by Daisaku Ikeda, President of the Soka Gakkai International, after he gave a lecture at the Harvard-Yenching Institute on how Buddhist humanism can contribute to twenty-first century civilization. The central idea in that lecture was that peace, true peace, can be realized only through dialogue, not by force of arms or top-down agreement. When he established the BRC, he gave us a motto reflecting this vision. He hoped the Center would be the “heart” of a network of globally minded citizens, a “bridge” for dialogue on shared ethics among cultures and religions, and a “beacon” shining a hopeful light on paths to peace.

As you approach your Tenth Anniversary, has that vision been realized?

Well, that’s hard to say, because our founding vision — heart, bridge, beacon — is a vision of “being.” It’s an image of ourselves that we strive, and keep striving, to manifest. I think this inspiring image has given our dialogues, whether they’re spontaneous or published, a unique warmth, openness, and depth. But, probably because the founder’s vision is so poetic (and Buddhist), it can’t be realized once and for all. We can always become a bigger heart, a stronger bridge, a brighter beacon.

Given the state of the world, your job could be rather discouraging.

On the surface it could be very discouraging because I think we currently have an intensification of a war culture in this country, and it’s rapidly spreading around the world. But I take heart from an insight of the British historian Arnold Toynbee, whose dialogue with Dr. Ikeda entitled Choose Life was a great inspiration to me when I first began practicing Buddhism some twenty years ago. He said that the underlying trends that really shape history appear in the cultural depths among the people as they live their lives, not in the day-to-day newspaper headlines. In fact, newspaper headlines can be a distraction. This idea has helped me to stay focused on the long slow work of cultural change. Fundamental shifts happen through dialogue and building communities of learning among people of various backgrounds—something that never makes the headlines.

Has the BRC become what you hoped it would be in 1993?

People have come to appreciate the Center’s commitment to bringing various cultural perspectives together. People always remark on the fact that we really do bring women into the dialogue much more than they are included elsewhere, and on the way we always strive to represent a cross-section of cultural, secular, and religious views. This has been intentional and it has led to numerous collaborations. That’s definitely an accomplishment.

Along with accomplishments, I’m sure there have been many unknowns along the way. It might be interesting for readers to hear if any surprises stand out in your mind?

One of my biggest surprises came recently with the compassion and social healing seminar that we held with Judith Thompson in September of 2002. The seminar brought together people who had been on opposite sides of ethnic conflicts from all over the world and showed me how small group dialogue can create a space of trust — if it’s done very deliberately, not just for intellectual insight but with openness to an actual change of heart.

How will the compassion and social healing dialogue influence BRC programs in the future?

That’s in the process of unfolding. We continue to sponsor larger conferences and lectures, but not as many of them, and more often in collaboration with other organizations. This approach gives us more meaningful large events and also the opportunity to pursue smaller, in-depth dialogues with selected participants. These small seminars can be empowering for the participants and then radiate outward through their work and through our website.

So the website has become a rich resource for the BRC community?

Yes, and it receives over 600 “hits” every day. For us, this is a cost effective way of sharing dialogue with people who can’t be here with us; we’re careful to make it highly readable and up-to-date.

Early on, we decided that common values are what really need attention.

Virginia Benson

During the past ten years, the Center’s agenda has addressed global ethics, human rights, nonviolence, environmental ethics, economic justice, education for global citizenship, and women’s leadership for peace — and more. How have you focused the Center’s agenda to encompass the far-reaching mission of world peace?

Early on, we decided that common values are what really need attention. We may use different languages and different religious concepts to talk about them, but there is a common core of values. So, we decided to focus on four main values that are also part of the UN mission: human rights, nonviolence, economic justice, and environmental ethics. We made one of these values the theme of our programs, both publications and events, every two years.

How did you decide to shift the agenda after that eight-year period?

At the end of the eight years, we settled on three focal points that came out of this process of exploring common values. First of all, we realized that the Earth Charter, to which we were introduced when we worked on environmental ethics, expresses a common core of values. We recognized, as well, that it came about as a result of extensive grassroots global dialogue and that it embraces those four values I mentioned. This is how our support of the Earth Charter consultation process transitioned into our commitment to working with youth groups to bring to life the global ethic that is articulated in this most amazing “people’s treaty” called the Earth Charter.

Secondly, it was obvious that women’s leadership and women’s empowerment related to the values that we’ve been exploring, all of which are often associated with the so-called “feminine.” Our view is that by promoting women’s leadership for peace — which brings these values into play in society — we will contribute to peace by transforming our social processes and institutions. The Wellesley Centers for Women has become a great partner in our annual Women of Courage lecture series highlighting women in history and contemporary times who have stood up for human values.

The third area of focus is education for global citizenship. Education has been fundamental to the Center and to Dr. Ikeda’s vision for peace. But after September 11, 2001, as we watched the American people turn toward retaliation and war, rather than respond with concern for the rule of law and international cooperation, we became convinced that something absolutely vital is missing in our educational system: an awareness that peace is possible. How can people have the vision that war is not inevitable, that it might even be abolished, unless we learn about alternatives at an early age? That essential question forms the foundation of our current works-in-progress: a book on global citizenship education and also a curriculum project with high school teachers.

You’ve managed to draw some very inspiring and well-known people to the Center over the years. Who stands out in your mind as you reflect on this decade of work?

That’s a tough question, because I’ve been privileged to meet so many amazing people. But Steven Rockefeller has been particularly inspiring to me. He’s a paragon of patience! He listened to and deeply respected the views of so many people — worldwide — throughout the ten-year process of drafting the Earth Charter. I’ve been thoroughly impressed by his continued focus on that single document, his determination to perfect it, and the earnestness with which he has pursued this goal.

And then, of course Elise Boulding has had a tremendous impact on the Center. I would say that she is the person who has led us to a much fuller conception of peace. In my previous incarnation as a public policy analyst, I used to think of getting to peace or social change through political means. It wasn’t until I met Elise that I came to know someone whose entire life has been devoted to understanding the educational and cultural approach to peace.

Since 1993, the BRC has published ten academic books that have been used in over 135 college and university courses. This, combined with a substantive newsletter and the website, translates into a pretty wide reach for BRC publications. In what ways do you see the BRC reaching people in the years ahead?

We’ve been venturing into new territory in terms of our publications, starting with the website as I explained earlier. For example, after September 11th, we started to post previously published articles on our site under the heading “Perspectives on Terrorism and Nonviolence.” These views from all over the world offer approaches to peace that haven’t been showing up enough in the mainstream press. Also, we are now considering ways of conveying some of the exciting new work that’s going on in the field of restorative justice through a Web-based publication.

In terms of books, we have focused on common values across cultures and religions. For example, both Subverting Hatred (1998) and Subverting Greed (2002) explore a core value across several religious perspectives. Our next book will be edited by Nel Noddings and will address education for global citizenship, especially in the United States. Beyond that, we are working on activity plans that would introduce critical thinking around historic conflicts within the existing high school curriculum. So, the publications program is quite dynamic. While the program’s appeal is broad, we hope especially to keep producing publications that are valued in teaching and learning situations.

What are the strengths of the BRC today?

I would say that we have two main strengths. First, we have a track record. These ten years of struggle and accomplishment have built trust in the community. People enjoy themselves at our events. Professors use our books in their courses. The other strength has to do with the people who come to work here every day. We started with just a couple of staff members and have grown very gradually into a small-but-strong team of people who work together really well.

I would add that Masa Hagiya, who is the only other person besides myself who has been here from the beginning, and Masao Yokota, who is the president of the Boston Research Center, have both exhibited great determination for the Center to become what it is today. As liaisons with our founding organization in Japan, both have exemplified tremendous skill and patience. Having these two people with us from the very beginning has enabled us to grow while keeping Buddhist humanism constantly at the root of it all.

If you could wave a wand and change something, what would that be?

If I could wave a wand, it would be to know more, to experience more, to understand more about how to break the cycle of hatred and violence. The work we are beginning to do in the field of restorative justice offers powerful ways to look within and, ultimately, transform hurt, anger, and fear into compassion or even wisdom.

People often think of peace as an abstraction, but it sounds more like the hard work of personal transformation.

I realize now that a lot of real wisdom about war and peace comes from people whose voices haven’t been heard enough and whose initiatives haven’t been recognized enough. The biggest challenge ahead is to listen to, and magnify, the voices of people rooted in caring communities and not to let these voices be drowned out by “elites” and self-styled “experts.” The process of overcoming the oppression and suppression of voices for peace takes a lot of determination. As things worsen at a global level, more and more people of all ages are seeing that they need to have more courage to express the good within themselves, learn from others in dialogue, and join together in the slow but sure process of tearing down hierarchies and building a different sort of culture—a culture of peace based on an ethic of care and mutuality.

Looking back, can you identify any particular interest or influence in your youth that you feel prepared you for your role here as executive director at the Boston Research Center?

I grew up in a large family as the youngest of four children. There were different interests in my family but we always had great dinner table conversations. In fact, they were cultivated by my father who would encourage us to talk about current events. I was the youngest so I felt very privileged to be part of the dialogue and share my insights. I liked the spirit of equality, even then. I learned so much from my older brothers and sister and from my parents during those conversations, which stand out as peak moments in my childhood.

What is the best part of your job?

I think it is the opportunity to engage in dialogue with the remarkable people that we’ve been able to attract to the Center — scholars and activists and people of all ages and from various cultural backgrounds who have inspiring life experiences to share. Even in large groups, when we have a major conference, there have been moments of true dialogue, of true understanding. You go through a lot of preparation for a large conference to make people feel comfortable… and sometimes you get this crescendo when it seems like everybody in the room is just getting it. I love that. This experience gives me hope that the whole world could move in this direction — toward a profound sense of interconnectedness, of harmony with the “other.”