John D. Montgomery: Banning the Disillusionments of Our Age

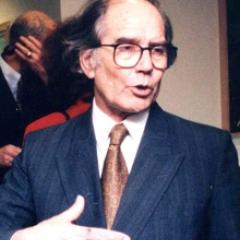

The late John D. Montgomery (1920 - 2008) was Ford Foundation Professor of International Studies, Emeritus, at Harvard University when he delivered these acceptance remarks at the Center’s 1st Annual Global Citizen Award ceremony (1995). His co-recipient that year was Elise Boulding. Dr. Montgomery was introduced by Professor Albert Carnesale, Provost of Harvard University and former Dean of the Kennedy School of Government.

Albert Carnesale’s Introduction

As I see it, my task tonight is to pose and answer three questions. Who is John D. Montgomery? What has he done? And why does he deserve the first annual Global Citizen Award?

I have had the honor of being a colleague of Jack Montgomery for more than fifteen years at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. Jack Montgomery is not only one of the founding fathers of the Kennedy School; he was, in fact, from his appointment in 1963, the first full-time professor of public administration at Harvard.

Let me say a little bit about Jack’s life before Harvard. He studied at Kalamazoo College, receiving both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree. After serving in the army during World War II, he volunteered his services for the Hiroshima Reconstruction Planning Commission. He then came to Harvard for further study, quickly became one of the leading scholars of what constitutes success and failure in rural economic development, and received his master’s degree in 1948 and his Ph.D. in 1951. Over the next decade or so, he was a Guggenheim Fellow; he worked in operations research at Johns Hopkins University; he was Dean of the Faculty at Babson College; he directed research on development in Africa at Boston University; and he was chief academic advisor for the National Institute of Public Administration in Saigon.

Then he returned to Harvard, where he has served since. He is now Director of the Pacific Basin Research Center, affiliated with Soka University of America, and he is Ford Foundation Professor of International Studies, Emeritus.

Let me digress here to add that this story is accompanied by a musical soundtrack. It is probably a Beethoven quartet, with a prominent and clear viola. Who else would arrive in Ibadan, Nigeria, learn that Carmen was being performed that evening, inquire about the number of violas, and have himself in the orchestra pit as the curtain opened?

Now that you have some idea of who Jack Montgomery is, on to the second question: what has Jack Montgomery accomplished in his field? Of course, one is tempted to ask, what field? Jack’s research is quite literally, figuratively, intellectually and metaphorically all over the map.

Jack’s primary insight, I think, is the link between what we call human rights and what is intrinsic to human dignity.Let’s say you were a student rummaging through the card catalogue in a major library. You would probably think that there were at least a dozen John D. Montgomerys: Developing countries? His name is there. Science and technology policy? His name is there. Land reform? His name is there. Political development? His name is there. Nutrition? His name is there. His publications are listed in all of those places. Analysis of how democracy can be introduced through military occupation, as occurred in Japan, Germany and Italy? Jack wrote the book. The disconnect between domestic and foreign policy? Jack was among the first to observe and analyze it.

All of this fruitful meandering has led, quite logically it seems, to human rights. Jack’s primary insight, I think, is the link between what we call human rights and what is intrinsic to human dignity. Thus, in a career that has since 1946 examined policymaking and the needs of the poor in more than ninety developing countries, Jack Montgomery has seen and is showing us the link between public policy—ours and theirs—and human dignity.

More recently, he has dedicated his own gifts and the research of the Pacific Basin Research Center to the study of “how policies to advance human rights affect the lives of individual citizens and thus enable them to achieve their own aspirations to human dignity.”

This leads us to and helps us answer the third question: Why is Jack Montgomery deserving of the first Global Citizen Award? Surely my responses to the questions about who he is and what he’s done more than demonstrate that Jack Montgomery deserves the Global Citizen Award. But let me give an even simpler answer. The simple answer is that Jack has and shares generously what I can only describe as “worldly wisdom.” He has the ability to form a sound judgment on virtually any matter.

Jack Montgomery—as a student, as a teacher, as a scholar, as an academic administrator, as a policymaker, as a traveler, as a viola player, as a colleague, and as a friend has always been, is today, and will be tomorrow, open to life, open to the experiences of others, and insightful in a way that clearly distinguishes him as a global citizen of the first order.

John D. Montgomery: Banishing the Disillusionments of Our Age

This occasion celebrates confident aspirations for a new and perhaps better century. It calls for buoyant optimism, clear vision, and a ringing endorsement of the human spirit. To reach that point, however, we must speak of the current despair, disillusion, and cynicism, to see if by examining their causes we can weaken their force.

My definition of our disillusionment does not echo the litany of current political complaints. I do not begin with declining family values, welfare dependency, the drug scene, or youthful crime, all of which I take to be symptoms rather than causes. I blame the Four Horsemen of the apocalyptic Twentieth Century. They are not the original Four—Conquest, Slaughter, Famine, and Death, none of which should be ignored—but we can find encouragement in one of the triumphs of our age, the fact that these specters have lost much of their fearsome aspect, though they have not disappeared altogether.

I see our own evil spirits as subtler and more pervasive than the original Four Horsemen, and even harder to control. I name them the Plunderers of planet and people; the Xenophobes, or perhaps better, the Ethnophobes; the Prophets, all of whom are false (God stopped giving exclusive access to truth some time ago); and the Vulgarizers, who are known to everyone who has a radio. These four are the ones who have brought us to our present despair; they lurk behind the evils and politicians curse and the pains that our underpaid workers suffer. The Plunderers are responsible for the drug scene and their upscale counterparts in the corporate world. (It is not the soulless corporations that plunder so much as it is their CEOs.) The Ethnophobes are moving their armies in central Europe and Eastern Africa and mobilizing their followers to hatreds actually hoping to bring about wars, foreign and domestic, more horrible than those of territorial conquest (170 million people have been killed by their own governments in the twentieth century, many of them stirred up by ethnic hatred). In their self-love, they are pursuing a definition that our own Henry Adams gave us, that “politics is the systematic organization of hatreds.” The Prophets, no longer satisfied with merely condemning society, are claiming divine inspiration for the bombs and poisons that destroy victims along with villains. The Vulgarizers are degrading the values that once informed our civility and uplifted our art, our music, our literature, and our political heritage.

These four evil spirits are the causes of our disillusionment. They are opening the cleavage between work and reward, and between beauty and entertainment; they are widening the division of mankind into ethnic or geographical enmities, they are substituting hollow religious zeal for individual responsibility and the voice of conscience, they are debasing the culture that is borne on the airwaves and carried in our bookstores.

As a political scientist, I have a special grudge against the Plunderers and the Xenophobes, who are attempting to set aside the judgments of history in the service of their greed. They would have us ignore a central discovery of our time, that countries do not progress for long by just becoming richer, more powerful, or more nationalistic. The countries that are showing the most sustained lines of progress are not necessarily the richest, or the most powerful, or the largest, but those in which governments have provided the greatest opportunities for the people who can use them best. Big, rich states often do less for the poor than small ones, with the result that the lack of equal opportunity degrades the level of national success. There is decay among countries that misuse their collective resources, however vast. They lose more than they gain by diverting investments from basic education and human rights. The countries with the best record today are those that are using public policy as a corrective for private abuse, especially women and stigmatized groups.

We are not acting out of public virtue when we fail to rebuke the noise of false Prophecy or the Vulgarizer’s din.We are not helpless before these specters. For each of them are rites of exorcism, individual and institutional. The universities and the centers of public enlightenment have resources unknown in the past to protect our fellow citizens from their ravages. There is also the growing power of information and communications which can yet be mobilized to erode the influence of the Xenophobes, the Prophets, the Vulgarizers, and the Plunderers. Today these institutions need spiritual, intellectual, and legal reinforcement. In the path of each of our horsemen there are institutional gates to restrain their attack on the public good, but they need support. To curtail the Plunderers, we have accounting systems, courts, union organizers, and tax collectors, but their work is limited to the authority assigned to them by corruptible lawmakers and an absent minded society. To restrain the Xenophobes there are peace movements and humanitarian instincts, but their voice needs reinforcement against the war cries of the intolerant. To denounce the false Prophets there are true ones who preach humility and justice, but their very self-restraint diminishes their efforts, for true prophets need true believers even more than false ones do. To outflank the Vulgarizers we offer courses in literature, art, and music appreciation, but we are not yet mobilizing modern communications technology to match their appeal. Thus we need not be intimidated by the charges of this light brigade. Yet the balance against them is not a force of nature; it requires the human hand.

What, then, must we do? First of all, we should be less tolerant, or, rather, more selectively tolerant. Of some things we ought to be intolerant altogether. When the Four Horsemen invade, there is no time for tolerance. We are not acting out of public virtue when we fail to rebuke the noise of false Prophecy or the Vulgarizer’s din. We defy our true nature when we pretend for the sake of civility to accept the unacceptable. We gain no eternal reward when we allow intolerable superficialities to blot out fundamentals. Trivial symbols are no substitute for troublesome realities. Who can imagine that real progress is made when we accept soft corrections instead of hard ones—when we modify gender in language while accepting unequal treatment of women? Or when we worship the colored cloth we call the flag or stand at politically correct attention when someone mouths the Pledge of Allegiance but defiles our national heritage of law and decency? Is it not legitimate for us to writhe in discomfort when a public figure disgraces the country by his manner of praising it? Can we not hope and strive that these symbols, superficialities at best, will be replaced by more substantive concerns 50 years from now? We should be intolerant of symbolic substitutes, not to rebel, but to affirm a deeper commitment.

How seriously intolerant must we be? Sadly, we must acknowledge to ourselves that there really are evil men about. The worst Destroyers in our midst, I think, are the Xenophobes, appealing to primitive tribal instincts. Hitler did not live in vain, I fear. It would not be difficult for anyone in this room to identify Hitler’s counterparts in our own time, seeking to splinter the structure of our polity in order to control all or part of it. In a violent world we must reorganize them more readily than we once did, and even if our civic order requires us to let them preach, justice requires also that we confine them to that role so that we can protect their victims. Once it was possible for us to allow individual and group morality to protect us against error, but as responsible citizens we can no longer rely on the market of ideas as an automatic corrective. As we approach the twenty-first century we shall have to face them down.

Even against the Vulgarizers we must act strongly to protect our cultural landmarks, and against the Plunderers we must labor to save our commons. These are duties and responsibilities we all bear; if public policy is to be our ally, we must use it to reclaim and reestablish our core values. Mediocrity is not enough for the twenty-first century.