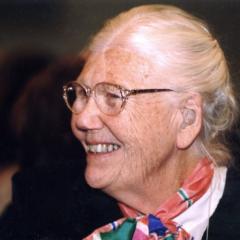

In 1995, Elise Boulding (1920 - 2010) offered these remarks upon being awarded the Center’s 1st Annual Global Citizen Award. Her co-recipient that year was John D. Montgomery. As Professor of Sociology at Dartmouth College, Dr. Boulding developed the nation’s first Peace Studies program. Her written works include Cultures of Peace: The Hidden Side of History (2000). Dr. Boulding was introduced by Kevin Clements, at that time Director of the Institute of Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University.

Elise Boulding Remarks

I’m overcome. Many of you in this room knew Kenneth.* I like to think he’s here with us now. I was unaware that Kevin was going to mention the “two hundred year present,” but that is a happy coincidence. While preparing these remarks I came to the conclusion that the only way I could talk about peace culture in the twenty-first century was by placing us in that larger present. I felt that using the two hundred present to talk about changing the world towards peace, justice, love, and sharing was the only way to build adequately on what’s already happening. After all, we’re not inventing peace from scratch. People have been at it for centuries. And to talk about the two hundred present as something we are present in, you and I, means that we have these colleagues and coworkers that link us to experience larger than our own life span.

The two hundred year present begins of course, on November 3, 1995, the year in which people who are celebrating their hundredth birthday today were born. The other boundary of the two hundred year present is November 3, 2095, when babies born today will reach their hundredth birthday. That period includes people who have been or will be part of our lives — from our grandparents and great grandparents through our grandchildren and great grandchildren, and we are all participants in the creation of a better world. Our Native American brothers and sisters talk about planning for the seventh generation, but I would like to extend that to ten — five generations back and five forward.

One of the things that astonished me as I began reading about the first half of this period — the end of the last century and the early part of this century — was what a vibrant movement there was in peace education. Teachers and community workers in Europe, Asia, and the Americas were just discovering a new way to teach. There was also the vibrancy and excitement of the movement for international law and for arbitration and dispute settlement. We assume we invented those things in our era, but they were already a big thing in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Right up to the present, there have been extraordinary developments — in problem solving, in peace building and in integrative developments, particularly the evolution of the people’s associations.

Just think, at the beginning of this century there were only two hundred transnational people’s associations and now there are twenty thousand! They are “thee and me,” linked through our local branches — across our states, across our countries, and across regions. Of course, not all NGOs are transcontinental, but many are. They are “us,” doing what we do in our communities, whether we focus on peace or economic justice or on doing better in our professions or making the business world function better. They are whatever we do in our communities of faith; what we do in concert with our brothers and sisters in networks that we can touch and feel, that we can meet in and work with.

We cannot do internationally what we don’t know how to do at home.The biggest discoveries for me came in the years when our children were small. I had to stay pretty close to home because the five came very close together. But one day I realized that all the things I was working on in Ann Arbor, where our children were growing up, had their counterparts in other places: the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, the League of Women Voters, our local Friends meeting, the YWCA, the Chamber of Commerce, and the Rotary. These all had local branches throughout the country; they had regional and even transnational affiliations. So that what I did in Ann Arbor, even while I was carrying a couple of babies around, could nevertheless be effective for linking with and working in collaboration with other people. It was a great discovery. Once I made it, I never felt tied down by those homemaker years. They were great years. It was just another way of finding out how to build world community locally.

Because I love networking, I have probably started more networking letters than anything else in my life; networking is the key word of our extended present. Look at the number of coalitions — all the peace organizational coalitions, the environmental coalitions (which got a big boost at Rio), and the ones that John Montgomery has worked with in the development field and the human rights field. What’s interesting is that they are all beginning to see not only that they can’t work alone (in the past every NGO wanted its own turf), they are discovering — and here the peace research community has really helped — that we can’t do just one thing at a time. We can’t do just peace, we can’t do just human rights, we can’t do just environment, we can’t do just development; we have to move in all those spheres at once.

We cannot do internationally what we don’t know how to do at home. And that’s why we have to work on developing our own cultures of peace. There isn’t any way around it. We’ve just got to do it. I’ll give a definition. I’m a bit nervous about giving a definition of peace culture, but it might help. And you can at least quarrel with it: A mosaic of identities, attitudes, values, beliefs, and institutional patterns that lead people to live nurturantly with one another, deal with their differences, share their resources, solve their problems, and give each other space so no one is harmed and everyone’s basic needs are met.

We can’t work for what we can’t imagine. So we have to be able to imagine, play, daydream about that peace culture. And Kenneth Boulding always used to say, “What exists is possible.” Because there are peace cultures — and we have all experienced islands of peace culture — it is possible. I don’t have time to share with you the various trends of this peace-building, but it has a lot to do with a growing commitment to community and to localism. With the rediscovery of community, children will become more visible. Age segregation will gradually dwindle away as children do more of their learning in community apprenticeships, and every citizen is a teacher. Just as there will be more emphasis for all ages on the practices of conflict resolution, and on meditation (listening within) and mediation (listening without), there will be more emphasis on nurturing the earth itself, on caring for local forests and waters. People will grow food where they live, whether in city or village. There will be more joy in work, more smaller-scale production, and more community celebration and play!

Do you want an indicator of a peaceful society? How much smiling do you see in any given hour?

Finally, I’d like to offer the image of Indra’s net, to remind us of the interconnection of local and global. In this beautiful image from Buddhist teachings, the cosmos becomes a vast jeweled net, each jewel reflecting every other jewel. It’s a hologram. Within each jewel is the complexity of all life. You and I are each inside a jewel. Whatever we do inside our jewel in the way of loving and caring and listening and healing — whatever we do inside our jewel at all — is reflected in the shining net of the cosmos. So, even as we stand in our own place, we all take part in the universe itself.

* Her husband, the influential economist, peace activist, and systems theorist Kenneth Boulding (1910 - 1993)