2004 Ikeda Forum: Walden and Beyond

The inaugural Ikeda Forum for Intercultural Dialogue, called “Walden and Beyond: Awakening East-West Connections,” took place on October 1 and 2, 2004, at the Center’s lecture hall in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Ikeda Forum was developed in close collaboration with Transcendentalist scholars and the Institute of Oriental Philosophy with the goal of tracing points of connection between the life philosophies of American Transcendentalism and Eastern wisdom traditions.

A particular emphasis on the ideas of Henry David Thoreau, as conveyed in Walden: A Life in the Woods, led to a focus on two key questions: 1) How can we awaken to all the possibilities that lie within the present moment? and 2) How can a profound transformation in just one person lead to social change?

Welcoming Remarks

Virginia Straus, executive director of the Center, welcomed approximately 140 people to the inaugural Ikeda Forum for Intercultural Dialogue on Friday, October 1, 2004, at the Center’s lecture hall in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Ikeda Forum was developed in close collaboration with Transcendentalist scholars and the Institute of Oriental Philosophy with the goal of tracing points of connection between the life philosophies of American Transcendentalism and Eastern wisdom traditions. A particular emphasis on the ideas of Henry David Thoreau, as conveyed in Walden: A Life in the Woods, led to a focus on two key questions:

- How can we awaken to all the possibilities that lie within the present moment?

- How can a profound transformation in just one person lead to social change?

This year, 2004, marks the 150th anniversary of the publication of Walden, which synthesizes Thoreau’s experience. As Walden illustrates, Thoreau was strongly influenced by Eastern traditions, especially Hinduism, though he was aware of Confucianism and Buddhism as well. A chapter of the Nichiren Buddhist text, the Lotus Sutra, was the only Buddhist text published in the Transcendentalist journal, the Dial. His openness to Eastern thought, combined with two years of self-sufficient living on the banks of Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts, led Thoreau to important insights — spiritual and philosophical — that subsequently influenced world leaders, including Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Nelson Mandela. This cross-fertilization of ideas forms the link with the life and work of Daisaku Ikeda, president of Soka Gakkai International (SGI) and founder of the Center, for whom the Ikeda Forum is named.

“Our intent is to honor Daisaku Ikeda’s extraordinary commitment to cross-cultural dialogue by focusing on a long-standing interest he has pursued,” said Straus in her opening remarks.

Center president Masao Yokota also offered an opening statement, in which he quoted from Dr. Ikeda’s message prepared for the occasion: “What is common to the ills that afflict us is the rejection of dialogue, and I firmly believe that the more severe the challenges we face, the more crucial it is that we persist in dialogue because dialogue has the power to break down the walls of mistrust, hatred, and division in the hearts of people everywhere.”

Surrounded by an exhibit of photographs of Walden Pond and environs by John Wawrzonek, the Friday evening session began with Alan Hodder, Professor of Comparative Religion at Hampshire College, who traced the Transcendentalists’ discovery of Asian traditions. Yoichi Kawada of the Institute for Oriental Philosophy spoke on “Buddhist Perspectives on the American Renaissance,” noting that “The history of Buddhism is the history of cross-cultural interaction.”

Saturday began with Emerson scholar and current president of the Emerson Society, Phyllis Cole of Penn State University, who illuminated the role of women in her analysis of “The Art of Conversation.” Bradley Dean, who has served as editor of a number of Thoreau texts, shared his thoughts on how Thoreau’s interests developed, before and after the Walden experience. Peace activists Judith Thompson and Zoughbi Zoughbi brought the concerns of the Forum into our contemporary world with their views on conflict, dialogue, and peacemaking. The practice of cultivating insight through experiential exercises was led by Sarah Conn of the Ecopsychology Institute and Leslie Gray, a Native American psychologist and founder of the Woodfish Institute. Personal insight into life choices was addressed by Paula Miksic, Northeast Women’s Division Leader for Soka Gakkai International. And a closing commentary by Professor Ronald A. Bosco of the University of Albany, State University of New York, spoke of Thoreau’s “deep sense of the personal” and how the Thoreauvian approach to life echoes the Socratic command of “know thyself” as the necessary point of departure for building a better world.

The great success of this Forum ensures future annual dialogues in the spirit of Daisaku Ikeda. Just as “new waves of knowledge [in the early nineteenth century] galvanized Western interest in Asia,” in Alan Hodder’s words, so might new conversations in the early twenty-first century help to shape global understanding. The Ikeda Forum for Intercultural Dialogue was developed for this purpose.

Friday Evening: Eastern Influences and Connections

Alan Hodder, Professor of Comparative Religion, Hampshire College

Turning East: The Transcendentalists Discover Asian Traditions

The first session of the Ikeda Forum on Friday, October 1, 2004, began with Alan Hodder’s lucid explanation of how and when awareness of Asian culture was introduced to America. Noting the eighteenth-century interests of Cotton Mather and Ben Franklin, in India and China respectively, he underscored the fact that “The Transcendentalists were not the first Americans to exhibit an interest in the people and cultures of India and East Asia.” And yet, he explained, “the Transcendentalists were certainly among the first Americans to affirm Asian religious traditions as a significant alternative to biblical religion.” Thus, the ways in which Americans came to understand Asian religious and philosophical texts were shaped by a coterie of literary and philosophical figures who lived, met, talked, and wrote from the bucolic surroundings of Concord, Massachusetts in the early nineteenth century.

But how did they come to an awareness of Asian thought? Professor Hodder’s talk seemed to “map” the answer to this question, beginning with reference to the India Campaign of Alexander the Great (327-325 BCE) and Marco Polo’s thirteenth-century journey to the Far East. When the Ottoman Empire, with its Islamic caliphates, took hold in the fourteenth century, it formed a kind of barrier to Western contact with the East. But as it declined, in tandem with the opening of the European spice trade in the early sixteenth century, exploration and commercial ventures became more frequent. Merchants, missionaries, and magistrates followed, and their combined interests established a solid colonial presence in Asia and a sense of connection between Western culture and the mysteries of the East.

As Hodder noted, a particular “cadre of British linguists and magistrates, under the auspices of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (founded in 1784), began turning out a wealth of scholarly monographs, learned articles, and English translations of classical Hindu texts” that led to a new understanding of India among Europeans. These translations were, naturally, the key that unlocked the power and wisdom of Hindu India’s classical texts, including the “Laws of Manu,” the Bhagavad Gita, the Samkhya Karika, and the Vishnu Purana. While these works made their way into European languages, other scholars began producing translations of classical Persian and Chinese texts, including the work of Sufi poets and the Neo-Confucian “Four Books.” In short, “This wave of new knowledge about Indian, Chinese, and Persian traditions galvanized Western interest in Asia,” said Hodder. Taken together, this “wave of knowledge” became known as the Oriental Renaissance and exerted a strong influence on the development of European and American Romanticism.

Not surprisingly, Ralph Waldo Emerson was exposed to these influences as a young boy in Boston, where ships returning from commercial expeditions to the East brought tales and news from India. He was also drawn to the East as a student at Harvard, where he wrote an assigned poem on “Indian Superstition” and showed great enthusiasm for Unitarian Press publications in which the Bengali social reformer, Rammohan Roy, figured prominently. Emerson is, furthermore, known to have come across excerpts of the Bhagavad Gita. When he became editor of the Dial in 1842, he worked with the young Thoreau on a new column, “Ethnical Scriptures,” that would serve as a vehicle for printing extracts of sacred Eastern texts (e.g. “Laws of Manu,” the “Four Books,” and a chapter on medicinal plants from Eugène Burnouf’s French translation of the Lotus Sutra) and, more importantly, for claiming the common philosophical ground between Eastern traditions and Transcendentalism. In 1845, with Charles Wilkins’ translation of the Bhagavad Gita, Emerson seemed to turn decidedly toward the East, even though some confusion remained among Americans between Hinduism and Buddhism, at least until the appearance in 1878 of The Light of Asia, a book by Edwin Arnold on the life of Buddha.

In other words, Emerson and other Transcendentalist thinkers lived and worked in a world where Eastern ideas were within reach. And it was to the texts that held these ideas that Emerson turned to illustrate his own philosophy. As Hodder pointed out, “In the Indian doctrine of karman, he [Emerson] found the perfect analogue to his cherished doctrine of ‘compensation’; in reference to spiritual transmigration, he recognized his own belief in ‘perpetual metamorphosis’; in the Upanishadic identification of atman and brahamn, he found sanction for his own idea of the Oversoul and the ‘God within’; and in the Hindu idea of maya, he found dramatic illustration of his key notion of ‘illusion.’

By contrast, Henry David Thoreau’s “conversion” to the power of Eastern philosophy came as an abrupt response to William Jones’s translation of the “Laws of Manu,” which he borrowed from Emerson. From this point forward, Thoreau took an avid interest in Eastern thought; among his books at Walden Pond was a copy of the Bhagavad Gita, which he mentioned frequently in Walden, along with other Hindu texts. Among the quotes from Walden that Professor Hodder shared is one that reveals the meaning of this work for Thoreau:

In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagavat Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions.

According to Hodder, the significance of such Asian sources “went far beyond mere illustration” for Thoreau. “As I argue in my book, Thoreau’s Ecstatic Witness, I believe this literature was crucial in helping Thoreau to make sense of the curious experiences of non-attachment and double-consciousness which, from an early age, he came to refer to as his ‘ecstasies’,” Hodder stated. Thus, Eastern thought allowed Thoreau to achieve new levels of self-understanding.

In a sense, the two themes of the 2004 Ikeda Forum go to the heart of self-understanding. Wakefulness and self-culture as a path to social change were both reinforced and enlarged by the connections that Thoreau perceived and articulated in Walden, a book Hodder referred to as “a wake-up call in a spiritual sense.” The metaphor of wakefulness, of dawn, has great meaning for Thoreau: “Morning is when I am awake and there is a dawn in me.” Clearly, in the poetic language of Thoreau, this is more than a matter of being physically awake.

For Thoreau, all success in life depended on consciousness, on the degree of one’s wakefulness; reality itself depended on the state of one’s consciousness. And just as Walden might be characterized as Thoreau’s wake-up call to the young America, the imperative to be and to stay awake shaped his entire approach to living,” said Hodder.

The second theme seemed to build on the first as Hodder interpreted it through Thoreau’s essay entitled “Resistance to Civil Government,” popularly known as “Civil Disobedience.” This work, which has influenced so many, is centered on the idea that an individual can make a difference, that self-culture can shape social realities. Thoreau can sound homespun and practical on this point: “It is not so important that many should be as good as you, as that there be some absolute goodness somewhere; for that will leaven the whole lump.” And he can also stir deep feeling:

I know this well, that if one thousand, if one hundred, if ten men whom I could name, — if ten honest men only, — aye, if one HONEST man, in this State of Massachusetts, ceasing to hold slaves, were actually to withdraw from this copartnership, and be locked up in the county jail therefore, it would be the abolition of slavery in America. For it matters not how small the beginning may seem to be: what is once well done is done for ever.

With these words, Alan Hodder concluded that for Thoreau “… self-culture — and this of course includes the cultivation of personal virtue — was not only a means to collective reform, it was the only means that held out any real promise of success.”

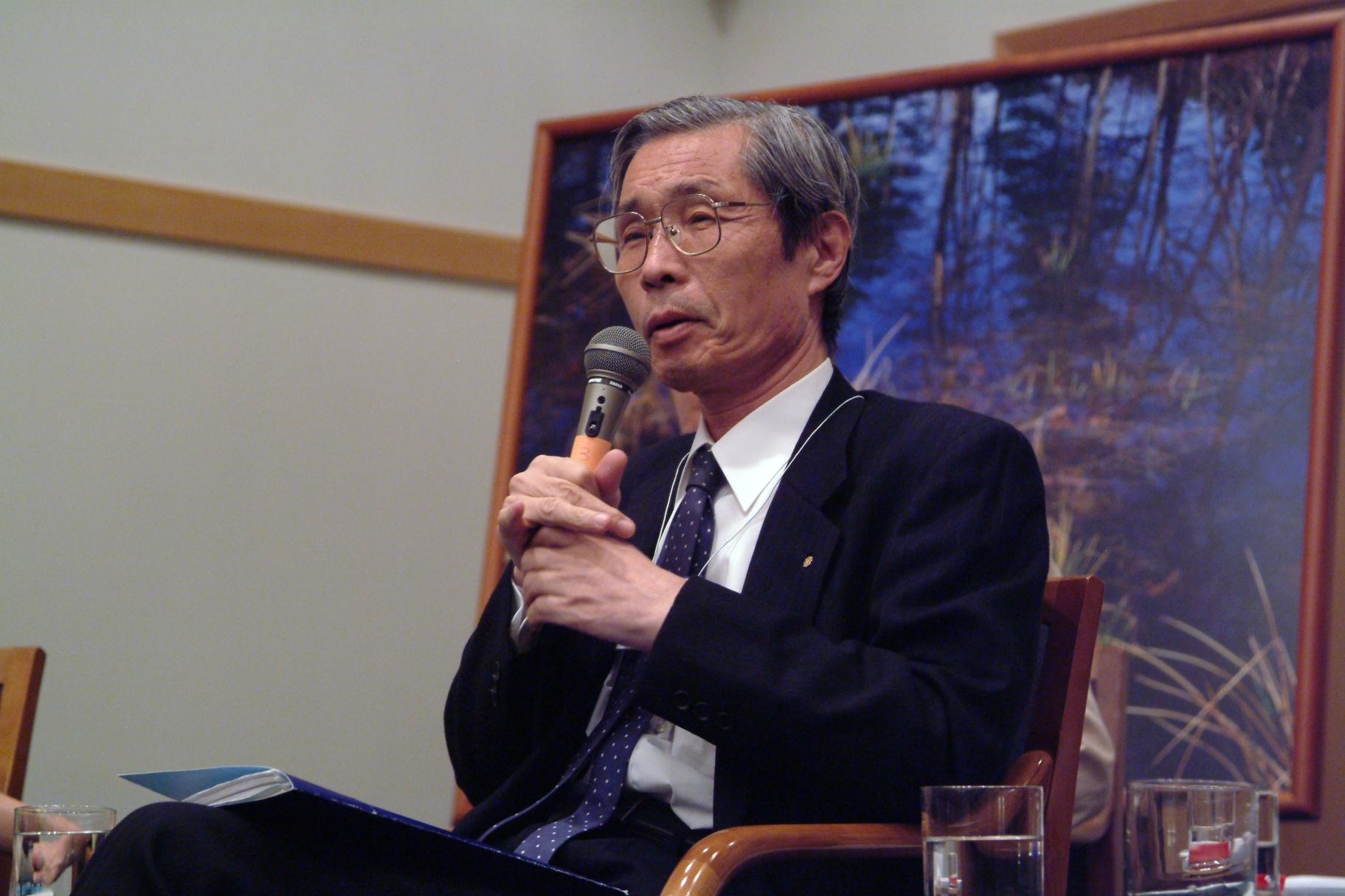

Yoichi Kawada, Director of the Institute of Oriental Philosophy

A Buddhist Response to the American Renaissance

Dr. Yoichi Kawada traveled from Japan to participate in the first Ikeda Forum. He identified the following as key concepts of Eastern thought:

- The oneness of the self (Atman) and the universal godhead (Brahma) in Indian thought.

- The oneness of heaven (nature) and human affairs in Chinese thought.

- The Buddhist concept of the oneness of life and its surroundings, and the principle that all aspects of phenomenal reality are embraced by the “life-moment” of the perceiving subject.

With these concepts in mind, Dr. Kawada then addressed three themes:

- The essence of Emerson and Thoreau’s response to Eastern thought.

- The nature of Shakyamuni’s awakening.

- The common ground between the Transcendentalists and Buddhism, Nichiren Buddhism in particular.

1. Emerson and Thoreau’s Response to Eastern Thought

Many people have found a fundamental unity in Asian thought. In Dr. Kawada’s view, Emerson seems to share this perspective when, in his Representative Men, he speaks of the universal attraction to “oneness” and the rapture of losing “all beings in one Being” as aspects of Eastern thought, even as he speaks of the diverse and finite nature of reality as the central concerns of Western philosophy. “If the East loved infinity, the West delighted in boundaries,” said Emerson.

Kawada noted that Emerson and Thoreau expressed great interest in the classics of India, China, and Persia. Emerson, in particular, was well aware of classical Chinese texts, such as the writings of Confucius and Mencius. When the ambassador of China visited Boston in 1868, he quoted from the Analects of Confucius in his welcome speech. However, for both Emerson and Thoreau, it was Indian thought that they were most familiar with, and within which they found the oneness of the self, Atman, and universal godhead, Brahma, that resonated with Transcendentalist ideas. In this context, Kawada quoted the Japanese Buddhologist Hajime Nakamura:

His [Emerson’s] emphasis on the Over-Soul as the inner definition of God in all things, and of a divinity residing in the soul of human beings corresponds with the teachings of the Upanishads and Vedantic philosophy.

Throughout Walden, Thoreau refers to Indian texts and philosophy. For example, he states that “the pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.” Also, for Thoreau, the symbolism and significance of morning as a time of awakening was crucial. “All wisdom awakens with the dawn,” he says, quoting the Vedas. For him, an awakened life was the life which we, as humans committed to living the most humane life, should lead. “We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which does not forsake us in our soundest sleep,” Thoreau writes. According to Dr. Kawada, the simplicity of Thoreau’s life in the woods was an earnest attempt to live the life of an awakened person of wisdom.

Both Emerson and Thoreau expressed interest in Buddhism. But as the translation into European languages of Buddhist texts, particularly those from outside India, lagged behind those of other philosophies, most Buddhist texts remained inaccessible to readers of European languages well into the nineteenth century. “This is significant, because the history of Buddhism is the history of cross-cultural interaction, as understanding of and appreciation for the meaning of Shakyamuni’s experience of awakening was successively deepened, refined and reinterpreted through encounter with the diverse cultures of Central Asia, China, Korea, Japan, Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia,” noted Dr. Kawada. “In this sense, one can only regret that translation and other limitations prevented a wider range of Buddhist texts from falling under the penetrating gaze of the Transcendentalists,” he added.

2. Shakyamuni’s Awakening

As he drew a parallel between Thoreau’s injunction of “Explore thyself!” and the experience of Shakyamuni in fifth-century India BCE, Dr. Kawada began with an essential question: To what exactly was he awakened and how has that given rise to the rich spiritual tradition that is known as Buddhism?

In response, Kawada explained that Brahmanism as a religion had become formal and ritualistic in Shakyamuni’s time. By contrast, his approach focused on human suffering, and led to his identification of “the four sufferings”: birth, aging, illness, and death. Through his example, Shakyamuni demonstrated that “all people can awaken to truth, liberate themselves from suffering, and live lives of genuine fulfillment.” Though born a prince, Shakyamuni gave up all the pleasures and privileges of that life in order to seek truth through an ascetic and meditative practice that he is said to have continued for six years. Finally, while meditating under the Bodhi tree, Shakyamuni was able to perceive and realize unity with the cosmic energy that is the font of all life.

“If we reconstruct this inner journey, I believe it can be understood as an exploration of the inner cosmos,” said Dr. Kawada. By moving beyond self-consciousness, he entered a “transpersonal” realm, a place where he was able to experience a concrete sense of unity and identification with all of humanity. This inner awareness extended to “a sense of oneness with the Earth itself, and with the planets and stars which, like individual human beings, undergo cycles of life and death — forming and coming together, dissolving and ceasing to be.” The universal or cosmic life that Shakyamuni achieved was, in Kawada’s view, “the fundamental essence of wisdom and compassion that supports and underlies all existence.”

Significantly, Shakyamuni’s awakening is recorded as having taken place simultaneously with the dawn of a new day, an expression of the synchronicity of the inner and outer cosmos. And it was his awakening that earned him the name “Buddha,” or “Enlightened One.”

With this story as a foundation, Dr. Kawada turned his attention to thirteenth-century Japan where the Buddhist priest Nichiren developed his philosophy based on teachings of the Mahayana text, the Lotus Sutra. “Nichiren was fervently committed to the idea that all people possess limitless potential and are in fact capable of the highest enlightenment,” Kawada said. Furthermore, Nichiren “saw reformation of people’s core spiritual orientation as essential to any attempt to relieve the enormous sufferings that plagued the society of his time.” This point of view led him into conflict with secular authorities, provoking harassment and persecution. And yet he continued to believe that lasting and meaningful reform of society would only come through the inner reform of individual lives. These ideas, which resonate with Transcendentalism, are also core to the Soka Gakkai, or Value Creation Society, that emerged in the twentieth century as a movement based on the teachings of Nichiren.

3. Common Ground Between Transcendentalism and (Nichiren) Buddhism

Clearly, the ideas of awakening and self-culture as a path to social change are concepts shared by Transcendentalists and Buddhists. In particular, Nichiren Buddhism focuses on inner reform as fundamental to social reform. By bringing Thoreau’s own words to bear on this common ground, Dr. Kawada illustrated the deep connection between the two philosophical movements. “To be awake is to be alive,” he said, recalling one of Thoreau’s most succinct statements. In the same sense, Shakyamuni Buddha is often referred to as “The Awakened One.” But perhaps more importantly, he encouraged “self-awakening” wherever he went. “You are your own master,” he said. “Could anyone else be your master? When you have gained control over your self, you have found a master of rare value.” This the “self” of Buddhism, like the “self” of Transcendentalism, is awakened, disciplined, and in harmony with all life.

“Buddhism refers to this as the Greater Self, the sense of oneness with universal life that we experience through bringing forth our Buddha nature,” Dr. Kawada explained.

By comparing the struggle of Nichiren to Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, founder of the Soka Gakkai, Dr. Kawada brought his comparison into contemporary times. As the Soka Gakkai has developed into an international movement committed to peace, culture, and education, it has created a new opportunity for Buddhist values and concepts to influence modern society. “While this is an engaged form of Buddhism, all these efforts are always based on the idea and practice of inner transformation, or human revolution,” Kawada said. “This may be the most important point of convergence between Asian Buddhism and American Transcendentalism, philosophies separated by great distances of space and time, but which resonate on the most profound levels.”

Q & A

The first question was for Professor Hodder, relating to Eugène Burnouf’s French translations of Asian texts: “Do you know if Thoreau read any of his translations, particularly the Bhagavad Purana?” In reply, Ronald Bosco confirmed from the floor that Emerson owned a copy of Burnouf’s 1853 translation of this text. (Thoreau was known to borrow books from Emerson’s library.) Professor Hodder added that Thoreau’s library contained a copy of Burnouf’s 1851 or 1852 translation of the Lotus Sutra. This would mean, necessarily, that whatever Thoreau used to publish the Lotus Sutra chapter on medicinal plants in The Dial in 1844, would have been an earlier edition. Professor Cole offered that it was Elizabeth Palmer Peabody who then translated this French translation into English and that is what appeared in the “Ethnical Scriptures” column of the Dial.

Ginny Straus commented that this column, which brought excerpts of Asian texts to an American audience, was a “huge project.” “Did they realize how big it was at the time?” she asked. Hodder explained that it was not, in effect, as daunting as it might seem since “the number of translations available were limited” and the column only appeared for a period of two years before the Dial went out of business.

Rick Wilson, a participant, then asked, “In what ways did Eastern influence live on into the twentieth century?” Also, he suggested that we might be seeing a cross-fertilization now between the successors of Transcendentalism and the more recent emergence of Buddhism.

Hodder replied that the development of “subsequent manifestations of Euro-American interests and Asian religions” was a “complicated story.” In brief, he suggested that understanding the influence of Asian religion in America is “one of the most lively and rich areas of American religious history.”

Dr. Kawada, noting that Buddhism has many texts and sects, stated that “The full picture of Buddhism has yet to be introduced to American society.” In support of Professor Hodder’s point, he agreed that the “deep commonalities between Transcendentalists and Buddhists could provide a positive opportunity for a renaissance of Transcendentalism in American society.” Kawada added that “As an Asian, I feel a particularly deep sense of appreciation to Thoreau for the impact that his thinking had on the life of Mahatma Gandhi and for his own nonviolent actions.”

Judith Thompson spoke from the floor as she “contemporized” the influence of Asian wisdom traditions with reference to American political leadership. She emphasized the link between contemplative practice and action, pointing to the “pervasive effect” of newfound Buddhist understanding on peace activism in the United States today: “I think this contemporary strain of how Buddhism is being internalized in this country is having a deep effect on peace culture in this country.”

In this context, Virginia Straus noted that Thoreau’s reflective time at Walden Pond had a profound influence on the writing of “Civil Disobedience.” Dr. Kawada supported this comment, and added that Josei Toda’s experience of awakening based on his reading of the Lotus Sutra has a parallel in Thoreau’s awakening based on his reading of Asian texts and how this “established a basis in his life of reform and change.”

Hodder also reflected on Thoreau’s contemplative nature and his activism. “It strikes me that Thoreau was not naturally inclined to be an activist,” he said. However, he explained, Thoreau was usually content with his walks in the woods, “But when issues of huge social and political momentousness thrust themselves into his life he found that he could not avoid them.” Thoreau’s opposition to slavery was one such issue. “Part of the reason he could not ignore it [slavery] was by virtue of the centeredness of his own contemplative experience,” said Hodder.

Following this thread, Professor Len Gougeon of the University of Scranton focused on actions of passive resistance, or “civil disobedience” in Thoreauvian terms, that came about as a result of such self-culture. He then raised the question of violent resistance with reference to the Harper’s Ferry incident and went on to observe that the Transcendentalists applauded the American Civil War as a way to deal, at last, with slavery. “Is this inconsistent with the influence of Eastern thought and philosophy?” he asked. “Or is there a time when high moral consciousness is going to lead to conflict and that conflict is going to precipitate resistance and violence?”

Professor Hodder expressed appreciation for the question and offered the example of the Bhagavad Gita as an Asian text that is a war book, a dialogue that takes place on a battlefield, and yet was read by Gandhi as a struggle between the self and the soul. He then deferred to Dr. Kawada who agreed with Professor Hodder’s explanation of the Gita and Gandhi’s understanding of it as an “internal battle.” Kawada added that he believed Gandhi also learned from the Gita “that war is always horrendous and brings nothing but misery and suffering to those who win and to those who lose.”

“I think he [Gandhi] also read very deeply into the wellsprings of Indian spiritual life and what he found there was nonviolence,” Dr. Kawada continued. “It was with that spirit that he read Thoreau, particularly ‘Civil Disobedience,’ as a methodology [of nonviolent resistance]. Implementing nonviolent resistance in India is Gandhi’s very unique contribution.”

Saturday Morning: Emerson’s World

Phyllis Cole, Professor of English and American Studies, Penn State University, and President of the Emerson Society

The Transcendentalists and the “Art of Conversation”

Professor Cole began by clarifying that while “Emerson and Thoreau are famous as celebrators of consciousness and its transcendence to divinity through nature,” they were also engaged in a lively community where “intense conversation with others” was part of ordinary life. “To Emerson, conversation was not a distraction from wakefulness and self-culture, but a resource towards these ends,” she stated.

Furthermore, conversation encompassed reading, particularly the reading of translations. It also included the exchange of letters and journals which now, according to Cole, comprise an “abundant and surviving paper-trail of minds connecting with each other.” And it was also face-to-face. All of these activities involved men and women. Indeed, the many dimensions of the Transcendentalists’ conversations represented the opportunity to “recognize each other and be recognized in turn, equally and reciprocally” within the context of philosophical inquiry.

Two settings served as the locus of conversation. First, Emerson’s house in Concord, Massachusetts, called “Bush,” was a place where friends, neighbors, and relatives often gathered, including his influential aunt, Mary Moody Emerson. It should be noted that Dr. Cole’s book entitled Mary Moody Emerson and the Origins of Transcendentalism: A Family History (Oxford University Press 2002) explores the relationship between “Waldo” and his aunt through a careful study of her letters and journals. Not only did she help to care for him and his brothers after the death of their father, she encouraged the young Waldo to read widely as she urged “knowledge of God in nature, retreat into solitude and resistance to conformity, and a poet’s vocation.” While she was, in many ways, “a contentious partner to thought,” Cole’s study demonstrates that it was Mary Moody Emerson who, effectively, taught Waldo to think. With her participation at Bush in 1835-36, the conversation must have been particularly stimulating.

Among other things, it was Mary Moody Emerson who introduced Emerson to Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, whose bookstore on West Street in Boston became a second gathering place for Transcendentalists, and a “center for inquiring souls,” according to Cole. This shop was, Cole explained, a place that was “perhaps even more central to cross-cultural reading and expansive group discussion” than Emerson’s home, because people could purchase and borrow books otherwise unavailable in the United States at that time. Not insignificantly, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody liked to quote Mary Moody Emerson who said, “Good conversation makes the soul.” And she enjoyed “soul-making” conversation in Concord and Boston, at Emerson’s home and at her shop. “Give me a friend who divines my needs,” she once wrote, after engaging in such conversation.

Other regulars in Emerson’s conversation group included Henry David Thoreau, Bronson Alcott, and Margaret Fuller. While Thoreau and Alcott were, for the most part, local figures at the time, Fuller was an adventurous spirit with worldly ambitions and a curious mind, a woman of “many moods and powers,” Emerson said. She conducted conversation classes at Peabody’s bookstore that delved into Greek mythology and gender relations. Amazingly, Fuller’s conversations were transcribed by a young student. “We have the closest thing to a tape recorder running that the nineteenth century could provide,” Cole explained. As a result, scholars like Cole have been able to understand the “deep sympathy” that developed among women in Fuller’s conversations and the intriguing ideas that emerged. For example, a woman named Sally Gardiner once suggested that if women could “… learn a new mental concentration, future poetry might emanate from their home and exert a power to bless and heal the nations so that ‘Men shall learn war no more.’”

Clearly, along with other “pioneering teachers,” like Elizabeth Palmer Peabody and Bronson Alcott, who founded the Temple School and a utopian community known as Fruitlands, Margaret Fuller had an important influence on Emerson. Their relationship, Cole observed, operated on many levels:

“Together they edited the Dial magazine during her visits to the Emerson house several times a year. She challenged his assumptions about women and men; she made him more political, as well as more mystical; she joined the Emerson circle and created another around herself.”

Fuller, like all the friends and family members in his circle, became a “resource for his vision” and a “forgotten minister” of his most powerful moments of intuition. In her talk, Cole illustrated Fuller’s influence with a quote from a letter Emerson wrote to her:

Will you not bring me your charitable aid? If my tongue will wag again, I will read you some verses, which, if you like them, you shall have for the Dial. At all events I will lend you my capacious ears, I will listen as the Bedoween listens for running water, as Night listens for the earliest bird, as the Ocean bed for the coming Rivers, as the Believer for the Prophet.

Cole’s analysis of this passage identified the ways in which “Emerson’s language likens this approaching talk both to nature’s forms of interdependence and to non-western forms of devout attention. His hope for spiritual renovation through talk seeks out this Eastern form of expression, perhaps impatient with the more ordinary language of New England pietism as he addresses a universal human condition.” In the same letter, he continues:

Come, o my friend, with your earliest convenience, I pray you, & seize the void betwixt two atoms of air the vacation between two moments of time to decide how we will steer on this torrent which is called Today. Instantaneously yours, Waldo E.

With reference to this letter, Cole explained that “The celebration of the present instant and its spiritual possibility is a signature of Emerson’s work, as well as the work of his contemporaries Thoreau and Whitman.” And yet that celebration is not conveyed as the result of solitude, but of dialogue. “Conversation is a way of knowing that allows for participatory knowledge of an interconnected universe, as when the Bedouin’s listening is analogous to night receiving the first bird’s song,” Cole stated.

Margaret Fuller died tragically in 1850, but others who conversed together with Emerson continued to work and thrive through the art of conversation. “Starting in 1848, first in Boston then in ever wider circuits of the Midwest, Bronson Alcott conducted conversations on the means of self-renewal and the divinity of human consciousness to groups of as many as 100 people,” Cole noted. He also taught an “extracurricular conversational class on Modern Life” at Harvard. Thus, for him, as for Fuller and others, conversation was a kind of action towards self-culture.

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody maintained the bookstore but expanded her reach to become a publisher, publishing the Dial. Through her work on translations and her personal Foreign Library, “she took a lead in the early introduction of Asian texts to American readers.” In fact, recent research has indicated that it was Peabody, not Thoreau, who translated a chapter of the Buddhist Lotus Sutra into English for the January 1844 Dial.

In conclusion, Cole emphasized the holistic nature of conversation, and related its “soul-making” power to the Buddhist concept of Dependent Origination, which holds that all things arise in relation to other things. Cole related the meaning of conversations conducted among Transcendentalists to a quote from Daisaku Ikeda:

Nothing and nobody exists in isolation. Each individual being functions to create the environment that sustains all other existences. All things are mutually supporting and interrelated, forming a living cosmos, what modern philosophy might call a semantic whole.

In this context, she described a dream of Elizabeth Palmer Peabody in which she achieved a true “intercultural spirit” through “a dream of ancient civilizations simultaneously present to her eye and ear…” In the dream, Peabody speaks back to voices of various divinities. “I live only by reaction,” she says. “Imprison me not in my own memory and imagination.” With this final image, Cole interpreted the dream and the dreamer’s response as a kind of vision, a deep understanding emerging from the years of study and personal connection with Emerson, Fuller, Thoreau, Alcott, and others. As if she, herself, were gazing through the dream, Cole declared that “What Peabody sees is the ultimate harmony of all world cultures in conversation.”

Q & A

John Halpern began by observing that the Transcendentalists seemed to be “intellectually fearless,” to which Phyllis Cole replied, “We live with limitations that erode our courage.”

Another comment addressed the possible connection between “the art of conversation” and the topic of nineteenth-century women conversing with spirits. In response, Cole explained that both were happening at the same time and spoke of the Fox Sisters of Rochester, New York, who were well known for their conversations with spirits. “This theme is constant in the 1840s and 1850s; there was a hunger for conversations with those beyond this world. For awhile this was believed to be genuinely and rationally possible.” Furthermore, she affirmed a connection with women leaders of the anti-slavery movement in Concord, and with Emerson’s wife Lydia. “There was a lot of kinship between the two movements,” she said.

Building on the discussion on women and spiritualism, Professor Len Gougeon of the University of Scranton suggested that the Transcendentalists’ motivation for seeking “a more holistic way of thinking and feeling” might have been their sense of alienation from a pragmatic and materialistic society. To support this point of view, he quoted Thoreau: “We’ve all become the slave-drivers of ourselves.” With this in mind, he proposed that women, and particularly women Transcendentalists, might have been even more inclined to seek such ways of thinking and feeling due to a “double alienation” from society combined with the greater role feelings played in their lives.

Cole agreed with this view, stating that “Certainly in cultural formation, women were permitted to feel, to have empathy and connection.” She noted that even today, women’s knowledge reflects “a different way of knowing” marked by connection. Given the sense of “doubleness” referred to by Gougeon, Cole agreed that “There was all the more reason for looking to God or the cosmos for unity.” And yet she also noted that nature and God would not be “the whole answer” for women, since they still were prohibited from full participation in society. Unlike Emerson, who walked away from Harvard College and expressed a lack of enthusiasm for voting, “Women didn’t have Harvard, they couldn’t preach, and they didn’t vote. So they looked toward things of this world too.” Ginny Straus observed that there was an irony in this since many nineteenth-century women found inspiration and encouragement for independence in Emerson’s work. Cole agreed that the irony was intriguing, especially given Emerson’s ambivalence about the women’s rights movement at the time, which was focused on the right to vote.

A final question came from Lavinia Weissman who observed that Thoreau and Emerson had empowered individuals to go inward, and thus “turn their backs on institutional life.” Her observation focused on the courage of Buddha and Thoreau “to reflect quietly” and derive strength from that, and then focus the power of that independence on social change: “I think women were seeing this paradox, the promise of independence and a way to gain strength.” She referred to the Twilight Club, which was an organization that brought thinkers like Emerson and Whitman into dialogue with contemporary leaders with the underlying purpose of changing institutional life. “With the power of this thought today, where do we go with peacebuilding to influence institutions like the UN or the U.S. government?”

In response to what she called “an enormous question,” Cole replied: “I think about models of courage among women from that time, people like Margaret Fuller and women who were engaged in the anti-slavery movement. They were all engaged in direct action for principles, which was a form of peacebuilding. From then until now, there has been a continuing history for us to learn about and build upon.”

Saturday Morning: Intercultural Dialogue Today

Judith Thompson, Peace Scholar and Convener of Dialogues on Justice, Compassion, and Social Healing, sponsored by the Fetzer Institute

Judith Thompson began by reading a poem written by Kaethe Weingarten entitled “The Image of the Shell.” The last two stanzas of the poem are as follows:

For compassion to lead to social healing, each one of us

has to be willing to put a shell to our ears and to let it rest

there awhile; a long while, or as long a while as we can bear.

We have to be able to put it down, and then pick it up again.

Or another, or another. Over and over again. And if we are

a shell, we have to believe that there are people who will

cradle us at their ears.

“May we all be shells and ears for each other,” said Thompson.

Inspired by this metaphor, and by Professor’s Cole’s talk on the “art of conversation,” Thompson expressed concern that “monologue seems to be replacing dialogue in political discourse” today. She also quoted Emerson:

[In] groups where debate is earnest, and especially on high questions, the company becomes aware that the thoughts rise to an equal level in all bosoms, that all have a spiritual property in what was said, as well as the sayer. They all become wiser than they were. It arches over them like a temple, this unity of thought…All are conscious of attaining to a higher self-possession. It shines for all.

In Thompson’s view, this passage points to the “collective mind,” or what Emerson referred to as the “Over-Soul.” In it, she explained, he saw “that transcendent moment when we stand in awareness of the greater whole.”

Turning to the theme of awakening, she noted that Emerson’s awareness of such moments provided one path to awakening through “group synergy” or “unity of thought.” From this, she concluded that intention was “of ultimate importance in determining whether or not a group dialogue will open to the emergent or simply recycle individual thoughts.” In short, Thompson’s experience in intercultural peacebuilding has demonstrated that the opportunity for transformational dialogue rests on the intention to be open and authentic.

The physicist David Bohm refers to dialogue as “… a stream of meaning flowing among us and through us and between us. This will make possible a flow of meaning in the whole group, out of which will emerge some new understanding.” Like Emerson’s point that those in conversation “become wiser than they were,” Bohm seems to see a metaphysical action and reaction at play when true dialogue occurs.

Thompson related these ideas to the work of the British mediator Adam Curle who began as a Quaker and later in his life embraced Tibetan Buddhism. It was his understanding of Eastern religious traditions that influenced his approach to peacemaking. In his book entitled To Tame the Hydra (Jon Carpenter, 1999), Curle relies on the metaphor of the many-headed mythological Hydra that Hercules must kill to fulfill his Labors. But when the head is severed, it grows back. In this book, Curle suggests that the modern Hydra has nine heads (rage, ferocity, greed, cruelty, hatred, lust for power, pitilessness, distrust, and illusion) and has grown increasingly “tenacious and robust with globalization creating a global culture of violence.” As he considers the meaning of the modern Hydra and explores how it might be tamed, he offers meeting and talking as a way to “save humanity’s joie de vivre and, indeed, humanity itself.”

“Here we find our peacebuilder, intercultural specialist Curle, tying together a number of our core questions,” Thompson observed. “Rather than the solitary moment of awareness one might achieve through contemplative practice, Curle, like Emerson, is referring to a force of mind arrived at via dialogue itself.”

She then turned toward the Middle East, to honor her colleague Zoughbi and to bring focus “to this anguished part of the world,” through the voices of Arab Muslim scholar and peace practitioner Abdul Aziz Said and the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber:

The purpose of life is to know this unity existentially — that is, in the midst of action, experience and spiritual practice — and not merely to seek distinction or salvation as an individual,” Said said. He has also described social healing as “the process of making your companions and the relationship that binds you together whole. It is inherently a dialogical concept combining multiple parts.

Thompson elaborated on Buber’s famous statement, “All life is meeting,” explaining that it “exalted not transcendence, but the immanence of relationship as revealed in the moment of ‘I-Thou’.” She pointed out that “While Buber did not focus his attention on group dialogue per se, his essential understanding of the potency of relational awareness, or presence, is filled with particular value as we approach our consideration of dialogue within conflict. For today, within my field of peace practice, most intercultural dialogue comes through the door of conflict, where one of the fundamental illusions separating groups is the monolithic, dehumanized image of ‘the other,’” she said.

“In Buber we find a crucial honoring of the relative and the absolute, the particular and the universal. For him, ‘God in man’ is not an abstract concept, but the person standing before you: this person in the here and now,” Thompson explained. She quoted Buber scholar, Maurice Freidman, in highlighting the complexities which accompany the relational framework of Self and Other, particularly when attempting to operationalize it in the context of conflict.”

“Buber’s ‘narrow ridge’ is not a happy middle ground which ignores the reality of paradox and contradiction in order to escape from the suffering they produce. It is rather a paradoxical unity of what one understands only as alternatives — I and Thou, love and justice, dependence and freedom, good and evil, unity and duality.”

In applying these insights, she referred to a process of 13 dialogue sessions between Israeli-Jewish and Palestinian students in 2002. The report on these sessions concluded that, “The dialogical moment in which a new understanding of the other is reached seems to emerge from a direct confrontation between the sides that breaks down the ‘double-wall’ of dichotomous monolithic constructions.” However, confrontation alone is not adequate to transform the relationship. “In such a dialectical process, the lack of mutual understanding and the extent of the lack of acceptance between the two parties have to first become clearly stated and visible to both sides. The parties then have to find a way to connect and relate to each other by developing more complex constructions of their own identity and of the other’s.”

Returning to Thoreau and the concept of being awake in a world of conflict, Thompson suggested that “merely being present to suffering as it is, as it unfolds” is an essential moral position, but action is required to truly move toward reconciliation. In closing, she enumerated seven pitfalls of dialogue as formulated by Palestinian lawyer Jonathon Kuttab:

- The assumption of symmetry

- Ignoring basic conflict issues

- Accepting the status quo

- Pressure to compromise genuine principles

- Pressure on the oppressed group to ease the task

- Co-option by authorities who would seek to de-legitimize the dialogue

- Dialogue as a substitute for action

With these points in mind, she added that asymmetrical situations often mean that those interested in dialogue come to it with very different agendas. The dominant group will often seek change from the inside out, while the weaker group will demand outward change to build trust. Thus, action becomes important.

“For Kuttab, the proper model for dialogue in conflict situations must include a sincere attempt to seek the truth without pretense, avoiding panaceas, being mindful about attempts to manipulate others into making statements simply for the sake of furthering dialogue, keeping one’s whole society in mind when in dialogue with members of another society and looking at dialogue as a first step,” Thompson stated.

Zoughbi Elias Zoughbi, Founder and Director of Wi’am, Palestinian Conflict Resolution Center

Mr. Zoughbi began with a description of his journey from Bethlehem to Boston. Along the way, he encountered numerous checkpoints and endured many security procedures in Israel and Jordan. “Every time I was asked ‘Where are you going?’ Every time I replied, ‘Boston Research Center [as the Ikeda Center was named at that time],’” he explained.

When the same question was asked by American Homeland Security personnel in Boston, he gave the same answer. But questions persisted. “What’s the Boston Research Center,” they asked.

“When they asked this question, I had a breakthrough,” Zoughbi said. “I saw the Center and the smiles of people there. And I replied, “I am going to the Community of Happiness.’” At that point, the security office began to smile. “This was my breakthrough experience in coming to this part of the world,” he reported, to laughter and applause from the audience.

Picking up where Judith Thompson left off, Zoughbi began with a riddle to demonstrate how action can lead to a breakthrough:

“There was a whirling dervish who was sitting by a river when a passerby saw the bare back of his neck and gave it a resounding whack. The person was full of wonder at the sound his hand had made on the fleshy neck of the other. In the meantime, the dervish, smarting with pain, got up to hit him back. “Wait a minute,” said the aggressor. “You can hit me if you wish. But first answer this question: Was the sound of my hand on your neck produced by my hand or by the back of your neck?” The dervish replied, “Answer this question yourself. My pain won’t allow me to theorize.”

“There are many levels of dialogue,” Zoughbi said, “and they are all important. There is the dialogue of words. And there is interfaith dialogue, which we need more of. But the third dimension of dialogue is action. And the fourth is the dialogue of common living.” With this framework in mind, he stated that in Palestine and Israel, more of the third and fourth kinds of dialogue are needed. “We need this holistic approach; we need to balance the imbalance,” he said. “We need to bring the powerful to their senses and empower the weak.”

Within this context, Zoughbi quoted Archbishop and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Desmond Tutu: “If you are neutral in a situation of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”

He also spoke of “collective responsibility” as he summarized the goals of a dialogue of action in the Israeli/Palestinian conflict:

- Palestinians continue their nonviolent struggle to end the occupation;

- Pro-justice and pro-peace camps in Israel continue their preventive nonviolent action to end their role as occupier;

- Support from the international community.

“We need to look at this issue from a very courageous point of view and shift the dialogue from guilt, blame, and victimhood to collective responsibility,” he said. Recalling the example of South Africa, he said, “There is no way to end this situation without collective responsibility. And it will get worse, because we live in a global village.”

He spoke of the importance of a “theme of courageousness,” quoting Tom Robbins:

You risk your life, but what else have you ever risked? Have you ever risked disapproval? Have you ever risked economic security? Have you ever risked real belief? Real courage is risking something you have to have to keep on living. Real courage is risking something that might force you to rethink your thoughts and suffer change and stretch consciousness. Real courage is risking one’s clichés.

“We need to be armed with real courage,” Zoughbi said, adding that “In Palestine and Israel, we live at the edge of fear, and we are all becoming hostages to fear and paranoia.”

Speaking of hope and courage as “two faces of one coin,” he said, “Dialogue without hope is nothing, and hope that is not risking is not hope.”

He then described a model of dialogue that he called the “Triangle of Dialogue.” The points of this triangle were labeled Dialogue, Action, Change. With this model in mind, Zoughbi stated that “We need to empower those who are ready for a different kind of dialogue.” He spoke passionately about how important Action and Change are and how necessary it is to expose atrocities as part of the healing process of dialogue. Finally, he urged that we revisit the past because “People are hysterical and historical.” He underscored the importance of history by suggesting a change in the educational system that promulgates a particular perspective of the past. “We need to start the unlearning process,” he said. “we need to look at issues from a point of view of inclusivity, mutuality, reciprocity.” It is not enough to talk about security, he explained, unless security is assured for all.

Finally, he called for justice as the “backbone of the process of dialogue” that will lead to change. “We need to focus on the needs of both societies rather than their ‘positions’.” Referring to activities among Israeli peace activists he said, “Voices that lead to action are rays of hope. But people of conscience, people of awareness need to act before it’s too late.”

With reference to the good work of many Israeli peace activists, Zoughbi emphasized the importance of building “a different community in spite of the walls [between Israel and Palestine].”

“Nonviolence should be the way and the strategy,” he said.

As his talk drew to a close, Zoughbi called for “a spirituality of transformation on the personal level, and societal level, and the international level” that would address issues of fear, psychology, and education in a more daring way that emphasizes constructive approaches of dialogue. “This kind of spirituality requires a collective responsibility,” he said.

In closing, he told a story that demonstrated his vision of “a true spirituality”:

The master was asked, “What is spirituality?”

He answered, “It is that which succeeds in bringing a person to inner transformation.”

The student was confused. “But if I apply the traditional methods, isn’t that spirituality?” he asked.

“No. It’s not spirituality if it doesn’t perform its function for you. A blanket is no longer a blanket if it doesn’t keep you warm.”

In other words, spirituality must change as the needs of people change. Otherwise, that spirituality is “merely the record of past methods.”

“We need a new spirituality that brings humility back and allows people to transcend hate, demonization, and death,” Zoughbi stated.

Q & A

Virginia Straus opened the discussion with a question directed to Zoughbi Zoughbi: How do you stay grounded and remain nonviolent?

In response, Zoughbi explained that “When you are angry, you must differentiate between the system and the person. Attack the system, but not the person. Be harsh on the system, but not on the people.”

He spoke of redemptive violence and urged that we be careful with this concept. “Violence dehumanizes people. But human beings have dignity and are created in the image of God. We need to respect this image and practice patience.”

“Also, we need a way to air anger, and so we have programs of trauma coping. In the Middle East, it’s not post-traumatic stress disorder, it’s ongoing, layer upon layer,” he added.

Kali Saposnik recalled the importance of conversation to Transcendentalists, suggesting the importance of sensitive conversation to educational reform, even in matters that are taboo. “How does such conversation happen?” she asked.

“They say that between two Israelis there are three opinions,” Zoughbi replied. “And many times between two Palestinians there might be five opinions.” As the laughter died down, his mood became serious and he spoke of the need among children and young people for a “diversity of ideas.” Regarding educational reform, he explained that, “The kids have no opportunity to have a more objective curricula. In many ways, the situation is worse than it was before the peace process.” Thus, he suggested, “It is the most important time for this to be happening. It is essential, because we are a democracy in the making.”

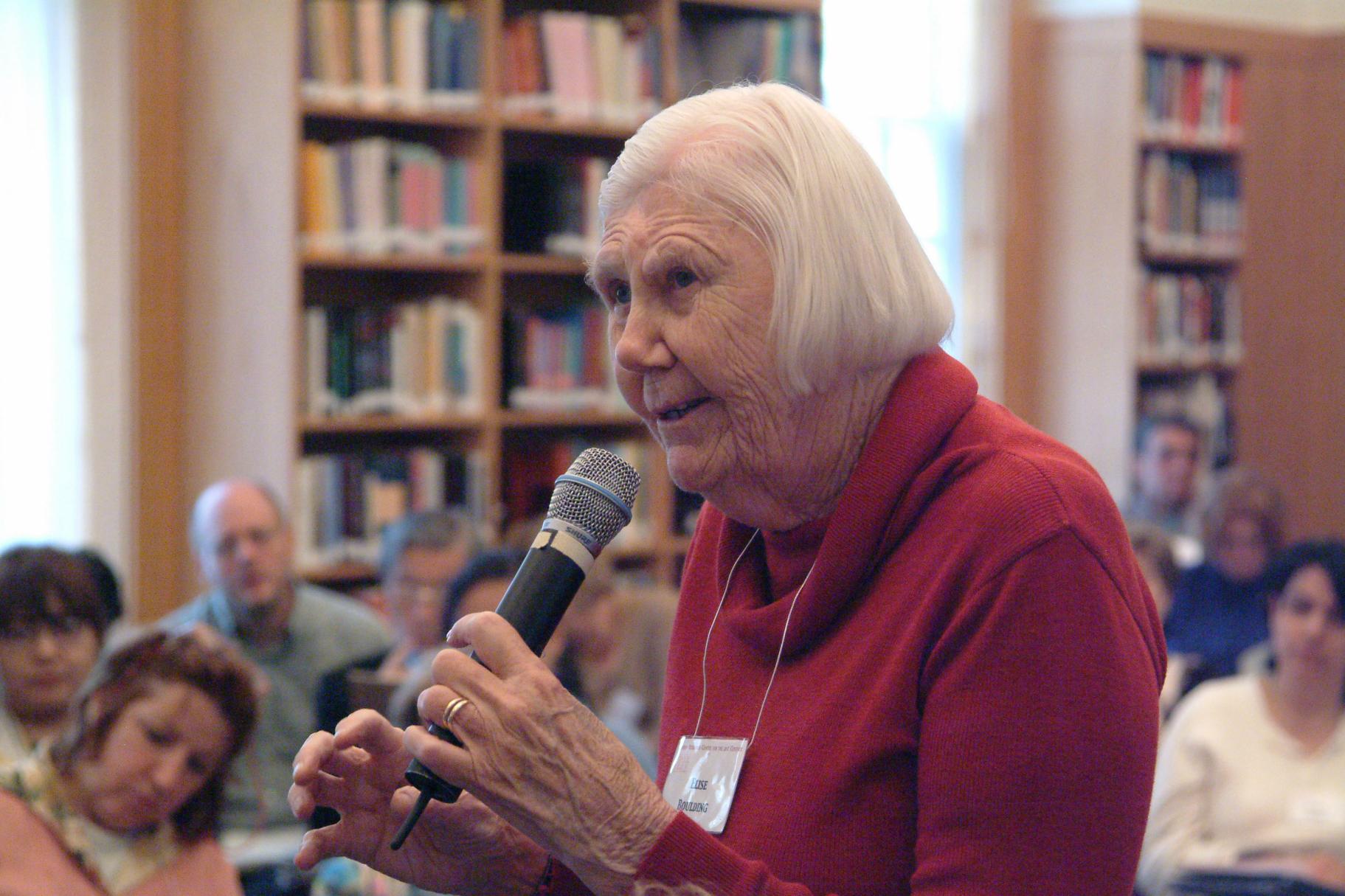

Elise Boulding entered the discussion with a characteristically incisive comment: “In a sense, the whole world is under occupation because of the omnipresence of the potentiality of war.” She urged those present to learn more about the growing organization called Nonviolent Peaceforce. “It’s an international group and we are citizens of the Earth,” she said.

A young man asked, “How do you keep up hope?” Zoughbi replied, “We choose hope; hope doesn’t choose us. And hope comes from engagement.” He also stated that, “Kids give us hope.” And finally, “Knowing you’re not alone is important for the psychology of people at war.”

Another Forum participant addressed “preventive peacemaking” with a question: “How would you approach the massive process of creating fear?” In response, Zoughbi spoke of the power of dialogue to alleviate fear because people sit face-to-face and learn to understand each other.

A poet in the audience whose work “couples the desire for peace with nature” suggested that poets are not being asked to play their part in helping to develop a “new spirituality” because they are seldom invited into dialogue due to the solitary nature of their work. “Maybe there are people writing who could help to create the new spirituality,” she said. “Maybe hope can be newly energized by creative minds and hearts.”

Another participant noted that based on history, the “oppressed will always ask for dialogue, but the oppressor is unlikely to listen.” In response to this, Judith Thompson suggested that human beings always have free will, in spite of history. “We draw our strength and understanding through reference to the past, through scripture, but in the end we must say: here we are in the here and now… what has happened in the past offers lessons, but those lessons are not determinants.”

The session closed with psychologist Leslie Gray speaking from the audience. “It’s easy to slip into the habit of confusing peace with passivity,” she said. “But passivity and aggression are both a failure of getting others to cooperate with you.”

Saturday Afternoon: Thoreau’s Path

Bradley Dean, Editor of Thoreau’s Letters to a Spiritual Seeker, Faith in Seed, and Wild Fruits

Independent scholar Bradley Dean introduced himself as someone who was here to represent “what Thoreau was about,” which he has become familiar with through his careful reading of Thoreau’s texts. Speaking informally with no prepared paper, Dean addressed five aspects of Thoreau’s world:

- Self-culture/Reform

- Eastern Thought

- Native American Life

- Human Community

- Nature

Self-culture

In an 1844 series of lectures on social reform in Boston, Thoreau spoke of “reforming the reformers.” In this context, Dean referred to the “pure audacity” of both Emerson and Thoreau and elaborated on Thoreau’s view of self-culture by quoting the “thesis statement” of his lecture:

“The disease and disorder in society are wont to be referred to the false relations in which men live, one to another. But strictly speaking, there can be no such thing as a false relation if the condition of the things related is true. False relations grow out of false conditions.”

Dean interpreted the word “conditions” to mean “everything that each individual is,” and suggested that if there is a fundamental falseness in the individual, false relations in society will result.

Later in the lecture, Thoreau speaks figuratively of a “pilgrim” he has met whose wide travels serve as a kind of archetype of the journey of humankind. On this pilgrim’s shield, he envisions the words “Know thyself.” Thoreau further expresses the wisdom of self-culture as he quotes a line from a poem: “Direct your eyesight inward and you will find a thousand regions in your mind yet undiscovered. Travel them and be an expert in home cosmography,” he said. Thus, self-culture was, for him, clearly related to the larger world of society.

In the “Economy” chapter of Walden, Thoreau asks, “What is your condition, especially your outward condition?” Dean interprets this “outward condition” as the body’s needs that must be met before the “inward condition” addressed in “What I Lived For” can become a priority. “Thoreau always begins with matter,” Dean said, before moving on to spiritual concerns.

Eastern Thought

Dean began by pointing out that most studies of Thoreau focus on “the Thoreau of the mid-1840s, before he went to Walden Pond.” In fact, Thoreau developed and changed his interests “dramatically” after 1847, and 1849 was an especially important “year of transition.”

“Eastern texts figured prominently in this transition,” said Dean. Furthermore, “He associates Eastern religion with a complex of images: antiquity, the past, night, the moon, dawn. The East causes him to look back.” Thus, Thoreau’s interest in the ongoing development of human beings begins, in a sense, with Eastern thought, which he associated with contemplation and abstract thought: “Behold the difference in the Oriental and the Occidental. The former has nothing to do in this world; the latter is full of activity.” In his journal, he explored his ideas about Eastern thought, particularly Indian divinities and texts, referring to “Hindoos” as those adept at “knowing, not doing.”

Native American Life

In contrast to his abstract associations of Eastern thought, Thoreau associates with Native Americans “their ability to live comfortably in this world,” a subject that became especially attractive to Thoreau after his transition year of 1849, when “Thoreau changed from being an Emersonian Transcendentalist to becoming a Thoreauvian Transcendentalist,” Dean asserted. He continued, “What I mean by that is that he more exclusively devoted his concerns to Nature.” Not only did Thoreau begin his Indian Notebooks in 1849, it was also then that he begins to “put away” his Asian texts. In 1855, an English friend sent him a “massive shipment” of Eastern texts. And yet, Dean observes, “There is no evidence that Thoreau read those books.” Rather, he worked from 1849 forward on projects relating to science and to the cultures of Native Americans, with a particular interest in the Algonquins prior to contact with “civilized man,” by which he meant prior to the arrival of Columbus.

Human Community

Dean addressed the question of Thoreau’s relationship with his community, noting that Emerson was clearly more connected to the Concord community than was his young protégé. In this context, he raised a question: “To what extent does wisdom literature come from people who are, in a sense, disssociated from their communities?” He further suggested that we tend to “mythologize” figures like Buddha or Jesus Christ, who stand apart from their communities and yet guide them at the same time.

Nature

“If the world were all man, I could not stretch myself, I should lose all hope,” Thoreau said in his Journal in 1853.

In the end, Nature was the over-arching attraction for Thoreau. As Dean’s work seemed to demonstrate, regardless of the various socio-cultural interests Thoreau pursued at various times, from “Civil Disobedience” to Eastern religions to Native American cultures, his central preoccupation was invariably nature; and this preoccupation became more exclusive after 1849. In Wild Fruits, a manuscript recently reconstructed and edited by Dean, Thoreau praises Nature: “[A]ll Nature is doing her best each moment to make us well. She exists for no other end. Do not resist her.”

Q & A

In response to Dean’s idea that figures like Thoreau eventually become “mythologized,” a participant likened Thoreau “to a court jester” who becomes a symbol. She stated that youth today are more interested in action. “They are no longer looking for heroes,” she said.

In response, Dean returned to Thoreau’s devotion to self-culture and his deep interest in the connection between Nature and human experience. He noted that Thoreau was well acquainted with death, as a result of his own brother’s death, and its connection to life. In Cape Cod, Thoreau said, “A man can attend but one funeral in the course of his life.” And speaking about “accident” and death in Walden, he wrote, “The impression made on a wise man is that of universal innocence.”

From the audience, Professor Len Gougeon of the University of Scranton, offered his interpretation of Thoreau’s relationship with himself and his community: “The real Henry David Thoreau was one fellow and the guy who wrote Walden was, in a sense, a character that he created.”

Professor Phyllis Cole also offered a comment, noting that in his cabin at Walden Pond, Thoreau had three chairs: one for solitude, two for friendship, and three for society.

Saturday Afternoon: Cultivating Insight

Organizers of the Forum wanted to contemporize some of the ideas that emerged in earlier presentations and offer an experiential component to participants through the work of Sarah Conn, director and co-founder of the Ecopsychology Institute at the Center for Psychology and Social Change, and Native American clinical psychologist Leslie Gray, who is also the founder and director of the Woodfish Institute.

Sarah Conn: Guided Reflection

Conn’s work focuses on the cultivation of an “ecological consciousness” that allows us to experience ourselves as part of the vast web of life and bring that experience into our daily lives. Central to this process is a deeper understanding of our relationship within Nature and an effort to dialogue with what she describes as “the more-than-human world” in order to overcome our “pathological individualism.” In her work, “symptoms” are perceived as “signals of distress in the larger context” that come through individuals as a result of their unique sensitivity to their surroundings. “Their distress contains knowledge,” she explained, “about their part in the whole, their contribution to collective wisdom, their participation in the world.”

She explained that her work addresses several essential questions:

- How can we as individuals, know ourselves as part of the living universe and at all levels?

- How can each of us know and act from our unique place in the whole web of life?

- How can we open to Nature’s wisdom?

Explaining that stepping back from our “habitual” ways of perceiving the world is a key aspect of her work, Conn invited those present to close their eyes and participate in a guided mediation inspired by Joanna Macy and Delores LaChapelle. She emphasized that “memory and imagination do not have to trap us,” noting that both can open us to “expanded ways of knowing” and to “inter-species dialogue.”

She then led the audience into a quiet place of reflection and connection through the guided imagery focused on inner awareness. “Let your awareness drop deep within you, like a stone,” she said, “sinking below what words can express, to the deep web of relationship that underlies all experience.” She identified this place as “the web of life in which you have taken being and which interweaves us all through space and time.” Through measured breathing, silence, and a deep awareness of energy within, each person was made to feel sustained by the forces of nature “like interlacing currents.” Conn articulated the ways in which these currents or “filaments of connection … extend beyond this room, this moment” and are known to each being. “There is wisdom here about how to live together in community,” she said. “There is power in the flowing of this fluid net.”

She then invited each person in the room to recall a time “when you had a powerful experience of relating to the more-than-human world, when a natural being presented itself to you on its own terms.” “What does this natural being have to offer you?” she asked. “What is its teaching? What might you bring from this encounter that might help you find your place as a citizen of this Earth?” By noticing what came to mind in response to Conn’s powerful questions, many felt that they had come a step closer to Thoreau’s state of being during his time at Walden Pond.

Leslie Gray: The Medicine Wheel

Gray introduced the audience to the pan-Indian concept of the medicine wheel, which she described as “an interconnected system of teachings relating the seasons and the directions to the cycle of life.” Through the medicine wheel, she explained, “you can locate yourself in the universe.” She added, “The medicine wheel is a model of a healthy mind. You can turn the wheel to get unstuck from dilemmas.”

She compared the medicine wheel to the stone circles containing ancestral knowledge and “important information” that can be found throughout the world. “The information is about who we are, where we are, and what we’re doing here,” Gray said. “The first thing the stones tell us about the universe is that it’s cyclical.” On the medicine wheel, the cyclical nature of life is represented by six directions: North, South, East, West, above, and below. “This is the totality, the all that is. No matter where you are, you are always in the center of six directions.” This totality can also be seen three-dimensionally “as an infinitely expanding globe,” she explained.

Additionally, each of the four directions is associated with a season and a particular power: East-clarity, spring; South-renewal, summer; West-introspection, autumn; North-wisdom, winter. The directions also correspond to time, recording the unending sunrises and sunsets, and reflecting key stages in the human life cycle: East-infancy, South-childhood, West-adulthood, and North-being an elder. She noted that each of these cycles “has a way that it goes,” a natural sequence and progression that has long been understood by Native American people as a kind of law.

Working with this basic understanding of the interconnected cycles and how they contribute to a balanced life, Gray invited each member of the audience to formulate a question, stand, and then face one of the four cardinal directions to seek an answer. As people turned in a clockwise (or “sunwise”) fashion toward each direction, summoning its powers, many discovered a fresh perspective and a new method of self-understanding.

Saturday Afternoon: Thoughts and Reflections

Concluding Reflections

Paula Miksic, Northeast Women’s Leader of Soka Gakkai International (SGI), was joined by Professor of English and American Literature at the University of Albany, State University of New York, Ronald A. Bosco, in offering closing thoughts and reflections.

Miksic spoke from the heart as she shared the personal story of her journey from her working-class roots in Westchester County, New York, in a family often plagued by discord and violence, to her role as Northeast Women’s Leader for SGI.

During her college years, Miksic became a political activist in both the Civil Rights and Labor movements. “Then I went to Europe to find myself,” she said, but returned home in 1968 after Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. “I was exhausted and discouraged by all the violence and injustice… and without the personal means to secure happiness. So I gave up. In retrospect, I chose not to be awake.”

She spoke of how her belief “in the goodness of people” was “buried” in an assortment of “unanswered questions” at that time in her life:

- How do I live day to day and implement what I believe?

- How can ordinary people like me infuse our lives with enough power, hope, wisdom, courage, and goodness to never be defeated and actually transform suffering into significant victory?

- What could I offer my friend and colleague who had a sick child and was mired with financial worries?

- How should I deal with my own broken family, not to mention the suffering caused by violence and oppression that afflicted millions of people I didn’t even know?

Although she initially resisted an invitation to attend an SGI discussion meeting in a small apartment in New York, the answer to these and other questions came through Miksic’s Buddhist practice. Over time, she came to understand the meaning of Josei Toda’s statement, “The Buddha is life itself.”

Through Nichiren Buddhism, “I was taught a way to access limitless potential,” she said. At the heart of her practice is the daily chanting of a phrase that means “harmony” or “the law of life itself”: Nam-myho-renge-kyo. This chanting, called gongyo, “rings out praise for life itself.”

“As a practitioner of Nichiren Buddhism, I give myself a wake-up call every morning and every evening,” she explained, likening her practice to the Transcendentalist concept of being awake.

She also compared self-culture to the Nichiren Buddhist idea of “human revolution,” which requires mindfulness and self-mastery of one’s inner life. Quoting Nichiren, she said: “While deluded, one is called an ‘ordinary human being,’ but when enlightened, one is called a Buddha.”

She also quoted SGI president Daisaku Ikeda on the meaning of this practice: “It is an act of reform, of human independence that unleashes subterranean wells of creativity. It is the method to harmonize the life of the individual with the life of the universe, and it is a proclamation of life.” Furthermore, “A great human revolution in the life of an individual can transform the destiny of an entire society and can make possible a change in the destiny of all humankind,” he said.

Miksic then shared two personal experiences that inspired her recently. Faye, a single mom, with an 18 year-old daughter and a two-year old grand-daughter was living under economic hardship as she struggled to survive with no more than a high-school education. Though a Nichiren Buddhist practitioner for a decade, Faye was very angry toward her daughter, whom she considered to be “an irresponsible teen-age mother.” When she participated in a group devoted to reading the dialogue between Ikeda and peace scholar Johan Galtung, Faye encountered great difficulty because English was not her first language. And yet her friends encouraged her to persevere in this effort at lifelong learning. As she pressed on and succeeded in reading and understanding this difficult text, Faye became joyful, enthusiastic, and was able to resolve her difficulties with her daughter, who is now attending college on a scholarship and beginning to practice Buddhism herself.

Another Buddhist friend, Carolyn, a mid-level diplomat at the UN, was recently passed over for a promotion “absolutely and clearly because she was female.” Many people became aware of this injustice and communicated it to her supervisors. In the face of this, Carolyn wanted to retire… and yet, feeling that she still had something to offer, she arranged a meeting with the UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, and expressed her concern to him that he was not fully utilizing her talents. She was, subsequently, appointed as an Under Secretary-General and is now leading a peacekeeping mission in Burundi. “At the same time, scores of women at the UN who had been held back in their careers got promotions, right after Carolyn’s promotion,” Miksic said.

Both of these stories seemed to demonstrate the power and possibility of cultivating oneself as a path toward transforming social realities and relationships.

In closing, Miksic returned to the wisdom of Daisaku Ikeda and quoted a passage in which he expressed the essence of his worldview:

“Each of us is born as a precious entity of life, as a human being. Our mothers didn’t give birth thinking, ‘I’m giving birth to a Japanese’ … or ‘I’m giving birth to an Arab.’ Their only thought was ‘May this new life be healthy and grow.’ Perhaps the clouds and winds, high above the blue waters of the Bosphorus are whispering among themselves as they gaze upon humanity, ‘Wake up! From here, it is clear that the world is one. You are all citizens of the Earth.’ There is no such thing as an American, no such things as an Iraqi. There is only this boy, this life called Bob who happens to live in America. There is only this boy, this life called Mohammed. Both are children of Earth and yet they are divided by the names of their countries and taught to hate each other. ‘Wake up!’ From this foolishness, this arrogance, and this cruel habit of passing hatred and resentment onto the next generation. We need to awaken to a common consciousness of being human beings. It is the spirit that says as long as you are suffering, whoever and wherever you are, and whatever your suffering may be, I also suffer.”

Ronald A. Bosco

Professor Bosco began with three observations based on his sense of the discussions that had transpired during the Forum:

- The pronounced gendering of conversations, in the nineteenth century and in our own time, seems to render dialogue “a form of epistolary seduction that often includes intellectual, imaginative, and physical components.”

- Today it appears that too many of our contemporary “wise people” are “distant,” that “wisdom in a culture is often not understood until that person who voices it has left us.” He suggests that Thoreau’s life which was relatively obscure in its own time has emerged with unusual authority since the 1960s to serve as a model of wisdom – a model for living deliberately in today’s world.

- The lack of poetry in academic and political circles is a present-day reality made evident by the language we use as opposed to the “prose poetry” associated with Emerson and Thoreau. In times past, he suggested, “poetic sensibility” allowed such people to be perceived as “seers who defined the moral center of culture and society.”

Bosco then proceeded with a more formal presentation entitled “ ‘Build, therefore, your own world’: Emersonian Reflections on the Concept of Global Individualism.”