2021 Ikeda Forum: "Becoming Wide Awake to our Wisdom, Courage, and Compassion"

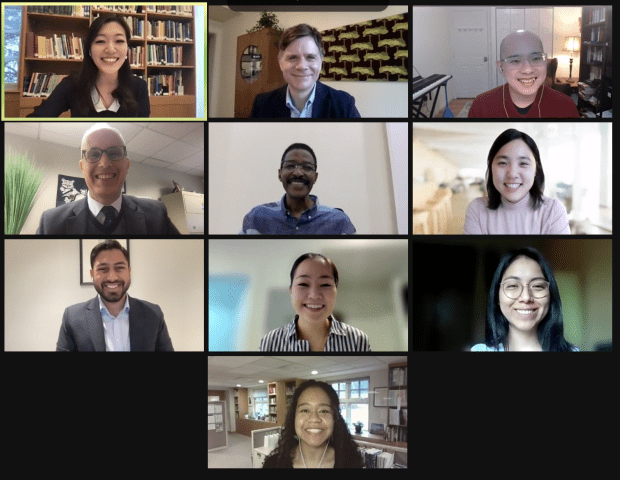

Dr. Awad Ibrahim and 2021 Global Citizens Seminar doctoral students present at the 2021 Ikeda Forum.

With nearly 250 participants attending from 27 countries via Zoom, the 2021 Ikeda Forum exemplified a uniquely 21st century version of global citizenship. Enabling so many people in so many far flung locations to dialogue face to face about topics of importance to humankind is a technological gift that holds great potential for fostering global cultures of peace.

Yet the core insight of the forum, which was based on Daisaku Ikeda’s conception of global citizenship, was that while the making of international connections is valuable, the journey toward becoming a true global citizen begins with each of us, no matter where we are located or our station in life, doing the inner work to develop our inherent wisdom, courage, and compassion.

Called “Becoming Wide Awake to Our Wisdom, Courage, and Compassion: Global Citizenship as Action and Identity,” the event featured introductory remarks from Dr. Jason Goulah of DePaul University, a presentation on the theme by Dr. Awad Ibrahim of the University of Ottawa, and a panel discussion with graduate students Handrio Nurhan, Meylin Gonzales, Seonmi Jin, and Archish Mittal. The forum also included breakout sessions during which participants engaged in dialogue in small groups on the topic.

The Spiritual Imperative of Wisdom, Courage, and Compassion

Ikeda Center Program Manager Lillian I shared opening remarks and served as MC for the proceedings. To set the stage, she said that Daisaku Ikeda “established this Center with the hope that people from all walks of life, all different faiths, ethnicities, backgrounds, and experiences, can come together to engage in genuine dialogue,” which Ikeda describes as “a ceaseless and profound spiritual exertion that seeks to effect a fundamental human transformation in both ourselves and others.” In this spirit, Lillian invited everyone to come together today “in sharing our thoughts and experiences with one another.”

By way of introduction to the forum’s topic, she said that while global citizenship isn’t necessarily the first thing that comes to mind as a source of hope given the challenges we are facing now, such as COVID-19 and myriad forms of social conflict, it actually makes sense when you consider Mr. Ikeda’s conception of it. As he explained in his 1996 address at Teachers College, Columbia University, “Thoughts on Education for Global Citizenship,” the root of all of our problems “is our collective failure to make the human being, human happiness, the consistent focus and goal in all fields of endeavor. The human being is the point to which we must return and from which we must depart anew.” And it is in this understanding that hope arises, since the capacity for positive change, even globally, grows from choices we make as individuals, here and now.

Following icebreaker activities and a video featuring people interviewed in Harvard Square on the topic of global citizenship, Center Executive Advisor Jason Goulah built on Lillian’s remarks by sharing more about Ikeda’s vision of global citizenship. Ikeda’s Teachers College address, said Goulah, represented a crystallization of decades of thinking on this topic by Ikeda. At the heart of the address is Ikeda’s identification of the three “essential elements” exhibited by the global citizen:

- The wisdom to perceive the interconnectedness of all life

- The courage not to fear or deny difference, but to respect and strive to understand people of different cultures and to grow from encounters with them

- The compassion to maintain an imaginative empathy that reaches beyond one’s immediate surroundings and extends to those suffering in distant places

It’s critical to note the context for this pronouncement, said Goulah. During this time, when the Cold War was winding down, Harvard’s Samuel Huntington had put forward his “clash of civilizations theory,” which held that the next world conflict would be based not on a battle between political worldviews but rather, said Goulah, between “people’s cultural and religious identities.” In this context, it becomes clear that Ikeda is identifying the qualities and behaviors that both disrupt any notion among regular people that this clash of civilizations is somehow inevitable and empower us to move past what Goulah described as the “identity dimensions that have historically and continue to divide nations and peoples.” Indeed, added Goulah, by “persistently cultivating these qualities with dialogue as our lodestar…. [a]n age of creative coexistence is always possible, especially with young people at the forefront, as we see here in this Ikeda Forum.”

To conclude, he went further into Ikeda’s conception of wisdom, courage, and compassion, including how they interact with and strengthen one another. First of all, said Goulah, Ikeda “maintains that possessing both wisdom and compassion ‘is the heart of our human revolution,’ or this inner transformation at the deep interiority of one’s life itself.” Crucially, we should understand that wisdom without compassion can be “cold” and even “perverse.” On the other hand, compassion without wisdom hinders our ability to truly “bring happiness to others.” Thus, said Goulah, “without a combination of the two we are even likely to lead others in the wrong direction and will not be able to achieve our own happiness.”

But it is courage that really makes Ikeda’s vision of global citizenship come alive. For Ikeda, added Goulah, it is “fear of difference” that hinders the emergence of wisdom and courage, triggering instead a “deep psychology of collective egoism” and taking “its most destructive form in various strains of ethnocentrism and nationalism.” Thus, “our own capacity for [both] self-actualization and global citizenship is fundamentally hindered by fear.” Indeed, said Goulah, Ikeda goes so far as to assert that “without courage, nothing happens.” With that, he wished everyone the courage to engage in meaningful dialogue and to take actions each day as global citizens.

You Don’t Just Wake Up Wide Awake

Dr. Ibrahim opened his presentation with an acknowledgment, homage, and thanks to the First Nations and indigenous peoples of North America upon whose lands we reside. Launching right into his talk he offered a series of “statements” to ground his observations. First, humans are “cursed” to the extent we don’t have a “readymade or already written script we can just simply pull out and read from or follow.” All individuals and even cultures are unique to the extent we can’t make broad generalizations. This diversity also provides possibilities, though. Second, because we don’t have a script to live by, if you take the initiative to write your lines, you are a poet. However there are also “strong poets” among us, the Gandhi’s, Mandela’s, Kings, and Ikeda’s, who not only possess “a radical vision, but a language that enables them to articulate that vision.” Most crucially, they are able to “think beyond themselves” to demonstrate courage and compassion.” Third, “because each one of us has a unique experience in life, what is common sense and so obvious to some will be a revelation to others.” As an example, he offered his experience, unsurprising to people of color, as a black man getting followed by security in stores. People open to such a “revelation” are in the process of “becoming wide awake.”

Fourth, when we talk about being awake to the experiences of others, we should not think of this as “simply an intellectual exercise,” because what we are talking about is “someone’s life” and “someone’s whole being.” So when we think about what is happening in, say, Myanmar or Ethiopia, we should avoid thinking in “abstract terms,” but rather to meet Ikeda’s challenge of thinking in terms of “human experience, human suffering, and human hope.” Fifth, it is wise to employ what Ikeda calls the “empathetic imagination” to “travel intellectually” while still being grounded in “some notion of humanity.” Interestingly, added Ibrahim, the philosopher Immanuel Kant “never left his place of birth” but he was “able to outline the framework of what we [now] call the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

Next, Dr. Ibrahim introduced a “typology of citizenship.” This typology proposes three levels or modes of citizenship: the personally responsible citizen, the participatory citizen, and the social justice-oriented citizen. The first “acts responsibly in his or her community,” paying taxes, obeying laws, giving blood, volunteering, and so on. The next is more actively engaged, actually organizing others to help those in need or to develop the economy or clean up the environment. They know strategies for achieving collective tasks. Finally, the citizen oriented to social justice is able to “critically asses social, political, and economic structures” to get below the surface to root causes. They work to “change established systems when they reproduce patterns of injustice over time.”

It is this last form of citizenship, said Ibrahim, that embodies his conception of being wide awake. The wide awake citizen is one who bears “witness” to injustice, said Ibrahim, respectfully acknowledging how this framing originated with the late Maxine Greene of Columbia University. Furthermore, “the wide awake citizen is one who is able to locate herself in a time and space and at the same time, questions the adequacy of that location.” In the US that means not turning away from realities such as “the genocide of the Native Americans,” or “the history of slavery,” or the “history of the suffering of women or the working class.” At the same time, emphasized Ibrahim, being wide awake also means being “fully aware” of such things as the “exceptional level of technological development and goodness in the US.”

Crucially, said Ibrahim, it is the “gifts” of wisdom, courage, and compassion that enable us to reach the most fully developed “level of awareness.” Or perhaps it is best to see them as “competencies” and “capabilities” that we work at and develop over time, he said. Indeed, “you will never just get up in the morning and rub your belly and say, I am so wide awake! Awakeness is a process.” The first step in awareness, said Ibrahim, is “to name your reality,” to “critically say I am here, and here is a complex place filled with challenges as much as it is filled with hope.” The next step is to no longer treat citizenship as a noun but rather as a verb, “something that we do every day it manifests itself every day and how we walk our talk how we relate to other people.” Finally, we understand that “here is where we start from,” meaning that global citizen is not “a free floating signifier. Rather, “a global citizen is someone who is deeply rooted in the local,” even when traveling. This means they have the capacity to think beyond their own local experience to link one’s reality to the reality of “other people in other places.” We are moved by compassion to think deeply and clearly about the world, in “a process that never ends.”

Dr. Ibrahim wrapped up his presentation with some thoughts on the relationship of wisdom, courage and compassion, followed by a video of a young practitioner of spoken word, hip hop poetry, expressing a message of hope and justice from his particular vantage point. If wisdom is an “intellectual ability” to accurately inform ourselves so we can act from an “informed location,” said Ibrahim, then courage is what enables us to act on our convictions with hope. But it is compassion that must guide us, since it is predicated on a “genuine desire to remove suffering.” Though he presented these qualities in a sequence, clarified Ibrahim, their relationship actually is “not linear.” Rather,

We are constantly moving back and forth. Here, the urgency of the moment calls for one of them. It is like a camera: we zoom in, zoom out. Sometimes we will find ourselves more within wisdom. Other times, we will find ourselves more within courage, and other times we’ll find ourselves more within compassion. In all cases, working through these cycles is how we end up becoming wide awake citizens.

Panel Discussion: The Lived Experience of Global Citizenship

Lillian I opened the panel discussion segment by asking each panelist to share a bit about what inspired them to participate in this year’s Ikeda Forum. Speaking first, Meylin Gonzales, who is a doctoral candidate in sociology at Harvard University, said that she is looking for ways to apply “these very profound and powerful concepts” of global citizenship to “my daily life and work.” Since this isn’t something she can do on her own, she thanked everyone for joining and said she is looking forward to the discussions.

Speaking next, Seonmi “Sun” Jin said she is from South Korea and pursuing her doctorate in higher education and student affairs at Indiana University. As a mother of a 3-year-old she has come to see that global citizenship isn’t just something that applies to her research, but also to her frequent interactions with “neighbors and friends in my local community.” Like Meylin, she hoped to explore what actions she could take toward global citizenship in daily life.

Archish Mittal thanked everyone for the invitation to participate and introduced himself as a graduate student in law and diplomacy at Tufts University’s Fletcher School, with a focus on the South Asian international political economy, which, he said, relates closely to global citizenship. But more specifically, his motivation came from reading the works of Daisaku Ikeda over the years, especially the dialogues. He has been inspired with how, even when engaging in the exchange of ideas with intellectuals and other leaders from around the world, “he had this ability to talk to the human being in front of him,” regardless of “whoever that person might be” and “devoid of their credentials and position.”

Handrio Nurhan introduced himself as “originally from Indonesia” and currently a 4th year doctoral student at Boston University studying anthropology. Specifically, his research concerns “ethical lives in the broadest sense,” including within Buddhist movements in Asia and Southeast Asia. So he has a keen interest in “ethical ideas like global citizenship and how people cultivate the tenets and ideas in their daily lives.”

Awad Ibrahim said that his motivations really related to the main points in his talk, specifically to explore what it means to treat global citizenship as a verb instead of a noun along with the idea that “there is no direct correlation between traveling and being a global citizen.” He said his core task is to look closely to understand the “root causes” of the conditions of his own life, locally experienced, and to make connections with the perceptions and experiences of others whenever possible. Even if those connections don’t appear, “at least I have the local in which to act,” he added. After these introductions, moderator Lillian I posed a series of questions to the panelists.

What aspect of global citizenship is most resonating with you now?

Archish Mittal jumped in by building on Dr. Ibrahim’s observations. First, he observed that while traveling and experiencing other cultures doesn’t automatically produce a global citizen, it can still be important, since “that really gives you an open mind when dealing with cultures and nationalities.” In all cases, our main imperative is to be “rooted in reality,” with the capacity to think globally while acting locally. Ultimately global citizenship is a choice, he suggested, a fact driven home for him by the fact that many of the diplomats and politicians he has met are “not really that globally minded and have a very narrow way of thinking.”

Sun Jin followed up by placing global citizenship in the context of her work as an education scholar. First of all, is the attitude that “compassion for others requires willingness to learn from them and to put in the extra effort to understand where they are coming from.” Then, in terms of curriculum, global citizenship means that students are encouraged “to learn about themselves,” but to always do so “in relation to others.” In fact, said Sun, reading America Will Be! by Daisaku Ikeda and Vincent Harding helped her to see that “self and other are not two different things.” Thus, in this context, wisdom means helping students learn “that they are reflection of each other.”

Do others have particular, concrete experiences to share?

Meylin Gonzales said that on a very immediate and practical level she has been able to help a variety of international students who have reached out to her recently on how to go about applying to and getting admitted to doctoral programs: “What is the process? Do you have any tips? Who should I talk to?” It’s been very gratifying, she said, to discover that she has something of real value to contribute in this way, showing how practical knowledge can become a form of wisdom. On a more theoretical level, she has been thinking about the qualities of global citizenship in relation to her research. She definitely feels that her work does a good job analyzing root causes, in this case relating to issues of gender equality among immigrants from Latin America seeking work. However, sometimes she feels she should be doing more to help more directly. Her advisors, however, have helped her see that focusing on her research is her main task now, and in this manner have helped her develop some “wisdom, courage, and compassion toward myself.”

If we were to put Daisaku Ikeda’s perspective on global citizenship into practice in our society now, what impact do you think it would have on people’s behavior and relationships?

Here, Handrio Nurhan joined the conversation by looking at his lived experience on a couple different levels. For anthropologists such as himself, it is the norm to go to different places and to try to inhabit those locales as deeply as possible. Yet, even a one or two year commitment will never bring one to the level of understanding as “someone born and raised there,” he said. So, a certain acceptance of limits is required. Limitations can also apply at a personal level. As someone who maintains his life in two localities—Indonesia and the US—Handrio feels “the difficulty and feeling of overwhelming complexity of just handling more than one,” adding “there’s so much complexity you just feel overwhelmed.” This is when he reminds himself to have “the courage to be persistent” and continue the effort. On an interpersonal level, he said we would all benefit from having the courage to engage more with people on the political and cultural “hot button issues” that people are avoiding now, and to engage with compassion when speaking “about these important matters.”

Dr. Ibrahim followed up saying that too often “we academics tend to disassociate ourselves from emotions.” But, if we consider Ikeda’s conception of the three attributes carefully, “we can see that “he is purposefully trying to make us think about why we do the things that we do, even as academics.” For Ibrahim, the truth is that it’s important to emotionally invest in “everything we do in our lives,” which means that in response to the question of what global citizenship has to do with our lives, “I would say everything.” Really, said Ibrahim, what he is doing is “debunking” that whole idea that research is “just an intellectual exercise” and proposing instead that we think of research as both “an act of love for what we do” and “an act of love for the community,” an act whose goal is “a better future for humanity.”

Key Takeaways

To wrap up the panel session Lillian asked for key takeaways and conclusions on why they want to “engage in this kind of life,” this wide awake path of the global citizen. Speaking first, Meylin said that she would “never forget” Ibrahim’s closing remarks of research as an act of love; “it’s not just useful but powerful,” she said. Beyond that, she said that given our interconnection as humans, global citizenship is a way to “embrace” reality rather than deny it. Sun Jin said that the main point for her is that “at the very core of global citizenship there is human dignity.” Speaking personally, she said that she has had to “practice courage” not only to address the dignity of others but “my own dignity too.” Further, global citizenship provides her with a strong frame for creating “allyship” with other people with “minoritized identities,” but also to see how value-creating she can be in all her relationships.

Handrio Nurhan said he was also very impressed with the notion of research as an act of love. One could also call that “compassionate research,” he said, which is important for “my own position as an anthropologist.” With this in mind, Handrio wants to not merely see a given community “as an object of study” but to really “work with them and commit to the causes I decide to study, because I believe in those causes and that there are contributions I can make.” A related aspect, he said, is to nurture the courage to honor “my own voice” within his research and field of study. Archish said that “what resonated with me the most is [that] we just need to continue having dialogues, we need to speak to our friends, our family, our classmates, and not just speak to them, but also listen to them and in the process really encourage them with our compassion.” And in the process, we should all seek “the courage to be able to hear out what people are going through, and what they’re suffering with.” To wrap up, Ibrahim reiterated his two core points: that global citizenship is an action and that global citizenship is not just an intellectual exercise but a way “to create human connection in so many ways.”

Conclusion

For this year’s Ikeda Forum, Ikeda Center Executive Director Kevin Maher offered closing reflections before participants broke into two Zoom “rooms” for discussion on topics such as: Which of the three qualities of wisdom, courage, and compassion resonate with you the most? Do you have a recent or past experience connected with that particular quality? How would you explain the concept of global citizenship to others who are not familiar with it? Can you think of how or in what ways the concept of global citizenship can, as we have heard it elaborated today, be applicable concretely in your own life?

Acknowledging the global reality of the event, Maher began his remarks with an inclusive “good morning, good afternoon, and good evening” to all who joined. He also expressed his “deepest appreciation to our all-star panel” and thanks as well to “all our participants, including many long-time friends of the Center.” Reflecting on the process leading up to the forum, Maher said “it has truly been a joy to collaborate together with this amazing group of scholars. In turn, these dialogues have inspired the Center staff to examine how global citizenship informs our work and lives, understanding that it is an orientation that needs to be cultivated continually through dialogue and connection with others.”

Maher then offered some reflections on Ikeda’s philosophy of global citizenship drawn from Dr. Goulah’s introduction to Hope and Joy in Education: Engaging Daisaku Ikeda Across Curriculum and Context. The first addresses the immediacy of global citizenship, “a practice of speaking to the complex human being in front of us and challenging the spirit of abstracting people into monolithic groups.” Closely related is what Ikeda calls the “sustained and courageous effort to seek out the good in all people, whoever they may be, however they may behave. It means striving, through sustained engagement, to cultivate the positive qualities in oneself and others.” These points resonate with Dr. Ibrahim’s conviction to see global citizenship as a not merely intellectual endeavor, said Maher.

Maher also shared three commitments from Mr. Ikeda’s 2013 Peace Proposal, “Compassion, Wisdom and Courage: Building a Global Society of Peace and Creative Coexistence”: First, the determination to share the joys and sufferings of others; next, faith in the limitless possibilities of life; and third, the vow to defend and celebrate diversity. “What a poetic statement, “Maher said, “to consider for how we might practice being in relation with others and become fully human.” Finally, he observed that “in listening to the wonderful comments from today’s panelists, I feel a deepened sense of hope and conviction that it is through these types of dialogues that we can became wide awake citizens and strong poets, and foster an ethic that emphasizes these qualities of wisdom, courage, and compassion as foundations for peace.”