In 2013 we helped to celebrate our 20th anniversary by gathering perspectives from diverse scholar-friends on our seven core convictions, which are all drawn from Daisaku Ikeda’s messages of guidance to us. Taken together, the perspectives of our contributors reveal the richness of the principles that guide us. Here are thoughts on Conviction Four: “Respect for Human Dignity & Reverence for the Sanctity of Life Provide a Baseline Ethical Standard.”

***

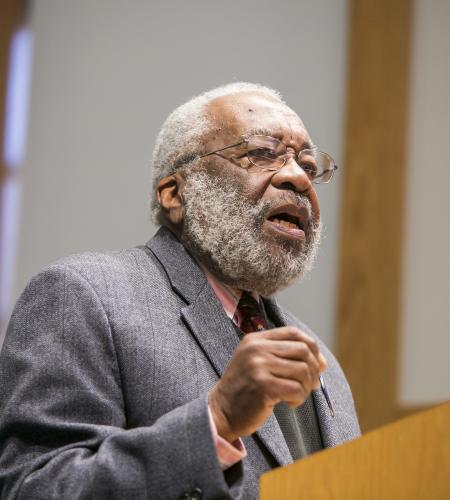

From Anita Patterson, Professor of English at Boston University and author From Emerson to King: Democracy, Race, and the Politics of Protest (Oxford University Press, 1997)

“The first [connection between Nichiren Buddhism and American Transcendentalism] is a respect for human dignity, a reverence for the mystery and sanctity of life. Both discover limitless possibility and the ultimate value in life itself. Both express belief that all life is endowed with an inherent dignity, that life in all its manifestations is unique, irreplaceable, and worthy of respect.” (Daisaku Ikeda, 2004)

I am especially drawn to this quote from Mr. Ikeda, having been inspired by his 2013 Peace Proposal where he calls for a new spiritual framework, founded on respect for life’s inherent dignity, that will help us to recover hope and strength. Mr. Ikeda’s statement made me wonder how I, as a teacher, can help students to cultivate reverence for the mystery and sanctity of life, and under what conditions our universities and other educational institutions will allow such respect for human dignity to flourish.

In “The American Scholar,” Emerson takes a good, hard look at the nineteenth-century workplace, and finds that, rather than being uplifted and inspired by the dignity of their labors, Americans were instead being worn down by dull routines that robbed them of their humanity. Emerson’s nightmarish description of American industrial capitalism gone awry, in an increasingly commercial and materialistic society that placed no value on human dignity, is worth quoting here at some length. “Man is thus metamorphosed into a thing, into many things,” Emerson says. “The planter, who is Man sent out into the field to gather food, is seldom cheered by any idea of the true dignity of his ministry. He sees his bushel and his cart, and nothing beyond, and sinks into the farmer, instead of Man on the farm. The tradesman scarcely ever gives an ideal worth to his work, but is ridden by the routine of his craft, and the soul is subject to dollars. The priest becomes a form; the attorney a statute-book; the mechanic a machine; the sailor a rope of the ship.”